2. The Archbishop’s Chateau

The archbishop’s chateau, a UNESCO World Heritage site where the original manuscripts for our December concert repertoire are housed, stands just off the Great Square (Velké naměsty) in the the heart of Kroměříž. The palace predates Prince-Bishop Karl II, the owner of the musical collection, but he initiated extensive renovations after the 30 Years’ War and purchased scads of artwork to display on its walls.

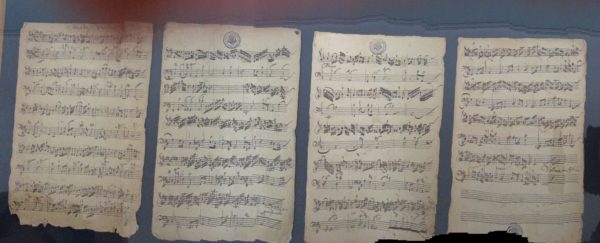

During one of my breaks from manuscript study, I got a private tour of the archbishop’s working rooms and galleries on the third floor, where the archive is also stored. One space was used for legal hearings, over which Karl would preside, and near to that is a tiered library with a pair of huge globes. All the floors were in parquet, and every ceiling was vaulted and decorated with forced-perspective, allegorical paintings. Some of the musical instruments from Karl’s time were also on display, along with a manuscript unique to Karl’s collection of a solo violin sonata by Georg Muffat (1653–1704).

The space I most wanted to see was the Sala Terrena, begun under Karl. It’s a three-room, ground-floor complex designed by Giovanni Pietro Tencalla (1629–1702) and themed after Roman mythology. Unfortunately, it was not open during my free time, so if any readers do visit, please share your photos or memories of the place with us! Tencalla also designed the Kroměříž Flower Garden (Květná zahrada), a short distance from the palace, which I did go to and was floored by its beauty.

I mentioned earlier that I was “set loose” in the palace, which would suggest a kid running around in a department store. In fact, I had a limited range within the palace in order to access the archive, but it was the first palace I’d ever set foot in, which was a thrill. My path to the archive was through a doorway in the central courtyard leading to a grand, granite staircase decorated with statuary at least up to the third floor. The music curator, Pavla Přikrylová, made the entire collection available to me which felt, in my mind, akin to being a kid running around in a department store.

The palace’s tower, visible from so many vantages throughout the town, has a walkabout below where its bells are housed, a feature shared with other Central European clock towers. These walkabouts serve as the perches from which trumpet-playing tower guards would have played to the town below. According to Dr Tanya Kevorkian, a professor at Millersville University who documents the intersections of music and society, these guards signalled a range of reference points for the townspeople around Central Europe such as the start of the day, the changing of the hour, and the closing of the city gates at dusk. The music they played included trumpet calls, hymns, and secular dance tunes. According to Dr Kevorkian, it’s likely that the Kroměříž baroque town hall’s tower also had tower guards. Kevorkian elaborates:

“In a small town the size of Kroměříž, one main guard tower in the center of town—the town hall tower—would have sufficed for sound to carry to all inhabitants. The palace tower could have doubled some of the town tower’s functions. Maybe tower guards or other musicians announced the arrival and departure of the archbishop and important visitors with a trombone/cornetto ensemble, and played once or twice a day for the benefit of the court. They may have played on holidays and other festive occasions as well.”

After Karl’s term, a fire destroyed part of the next bishop’s music collection, which would have represented the high baroque era, the period encompassing the styles of Corelli, Vivaldi and Handel, for instance. Fortunately, Karl’s collection was archived off-site, sparing the holdings of his music library from the flames. The Thirty-Years War and the fire explain why the collection in Kroměříž begins with the 17th century, the middle baroque, and the gap that would have represented the high baroque. The catalogue resumes with the classical era, and includes well-known composers like C.P.E. Bach, Haydn, Beethoven, Schubert, Mendelssohn, and Rossini.

There was clearly a tradition of music appreciation at the highest level in Kroměříž. In the course of assembling scores from part books (there are relatively few pieces in score form) from Karl’s collection, including pieces by obscure and even unnamed composers, I have yet to find a single dog. On the contrary, every piece has been a delightful surprise. While the number of famous-now composers is pretty small, the craftsmanship has so far been uniformly top-notch across the collection, to the extent I’ve been able to examine it.

I’m especially keen on the anonymous pieces in the collection, and I plan to talk about those in my next instalment. I’m so glad I overrode my impulse to pass those over!

You can find out more about the chateau and the pleasure gardens here:

Many thanks to Dr. Tanya Kevorkian of Millersville University for her insights on the clock towers, and to the Pew Center for Arts and Heritage for underwriting this exploration.