3. The Great Composer: Anonymous

Some of the names in Karl II’s music collection at Kroměříž are of known “thought leaders” in the field, composers whose music was widely known, respected and imitated by others. On our concert, that includes the likes of the stylist Giacomo Carissimi (1605–1674). To give an idea of the range, another influential composer with music at the archbishop’s chateau not represented on our program is Georg Muffat (1653–1704), who helped shepherd French style into the German-speaking lands.

There are also the composers on our program who are better known to a more niche audience, like the experimental Giovanni Valentini (1582–1649), Kroměříž’s capellmeister to Karl II, Pavel Vejvanovský (1640–1693), who was steeped in Czech folk music, and the millenium-child mystical poet/composer, Adam Michna (1600–1676), whose music is still sung in the Czech lands on holidays. More obscure still, even among cognoscenti, Father Jacob Rittler’s (1637–1690) music, which is uniformly excellent, lives exclusively at the archbishop’s chateau.

And then there are anonymous pieces from the collection that we’ll play. These turned out to be the biggest surprise of the music I looked at, all of such high quality that three of them made it onto our program: a sonata for recorders and strings, a chaconne for trumpet, recorders, and strings, and a Magnificat setting. These gems constitute most of A Czech Christmas’ second half.

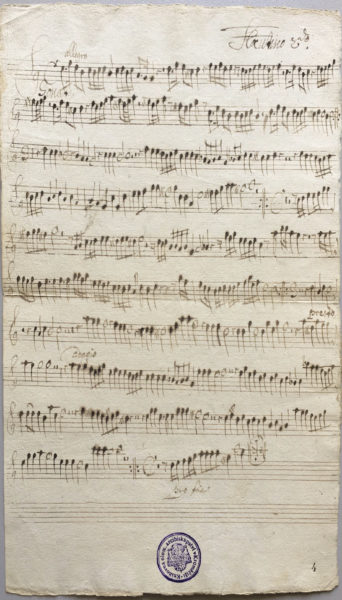

The first surprise was the sonata for two recorders, two violins, viola, and bass with continuo.

Its inconspicuous labeling, which described only the instrumentation, didn’t prepare me for an ingenious, instrumental polychoral romp. The two recorders and viola form one choir, while the two violins and bass form the other. The continuo plays with both. It’s a super chatty-sounding piece organized largely over a call-and-response approach. For instance, the recorders-viola choir plays a snippet of theme at the opening to which the strings choir responds. Eventually the choirs overlap and develop that initial snippet together. It’s a marvellous instance of the old-school Venetian polychoral tradition from the late Renaissance with newer Italianisms that seem to come from the last third of the seventeenth century. The musical notation looks like it could have been a copy by Vejvanovský.

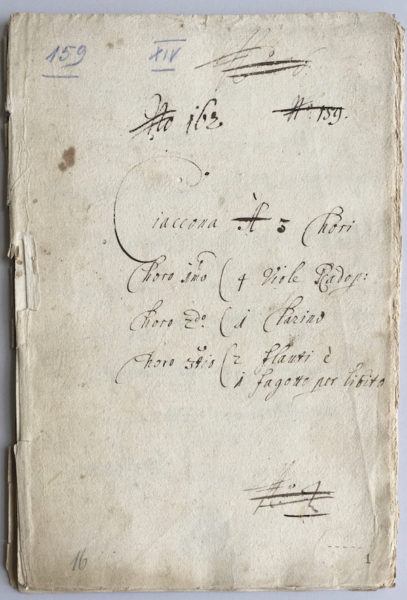

A “Ciaccona a 3 cori”, or for three instrumental choirs, is the other anonymous instrumental work on our program. The jacket of the manuscript in Kroměříž describes its choirs as string ensemble (choir 1); trumpet solo, here called “clarino” (choir 2); and two piccolo recorders with bassoon, which we’ll swap out for theorbo (choir 3). A ciaccona or chaconne is based on a fixed-length phrase, often a repeated bass line or harmonic progression, with variations. This one draws not only musical variation in the abstract, i.e., melody, harmony, rhythm, etc., but also on orchestration, with various combinations of a rich, 4-voiced string ensemble, the warm glow of a single natural trumpet, and the chirpiness of a pair of octave recorders. Plus continuo. It also has an allemande, a stately dance form used throughout the middle and late baroque, smack in the middle of it.

I would be hard pressed to choose between the chaconne or the sonata as the more charming piece.

The anonymous, grand, affective Magnificat, for four voices with string ensemble, is one of the rare items from Karl II’s manuscript collection for which there is a score as well as a set of parts, and is, in my opinion, the star of this program’s anonymous works, and possibly of the whole program. It is a late-sounding piece as compared to everything else on the program, likely from near the end of Karl II’s life. Given the Habsburg court’s mania for all things Italian and the music’s quality, it would not be surprising if this piece were eventually attributed to an important composer from Italy who bridged middle- and high baroque approaches, someone like Alessandro Stradella (1639–1682), for instance.

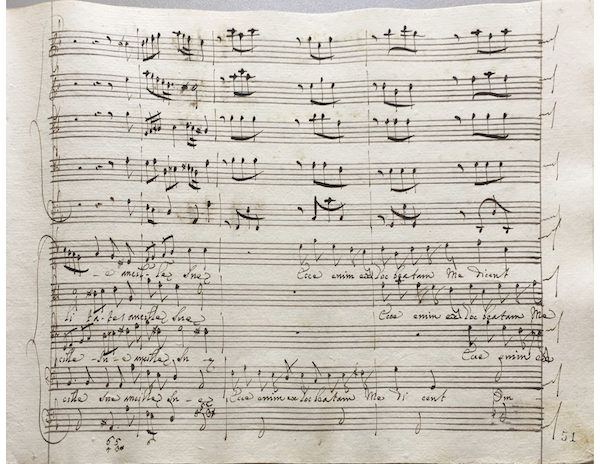

The score and parts are at slight odds with one another. The score shows both a bass of the string ensemble—two violins, two violas and bass—that is independent of the continuo bass. The string-ensemble bass plays in detailed rhythms specific to the activity of the violins and violas, rhythms that frequently diverge from the continuo’s more generalized rhythms. But the bass-family instruments in the parts—organ, theorbo, cello and contrabass, all have identical notes that agree with the continuo of the score. If a string-ensemble bass part also existed, it is lost. But I think there likely wasn’t one in this set of parts.

I suspect that this Magnificat was performed more than once at Kroměříź back in the day. This is because the basses are generally identified as “basso” or “violone”, the common nomenclature of the time for Italian and italianate pieces. The intended instrument for this time is bass violin, a member of the violin family larger and deeper sounding than a cello. The cello began to become more common late in the seventeenth century, so its specification in the parts may reflect a practice from later than when the score was created.

Many thanks to the Pew Center for Arts and Heritage for underwriting this exploration.

Image 1: Recorder 2 part for the anonymous Sonata for 2 recorders, 2 violins, viola and bass, credit Archbishop’s Chateau, Kroměříž, Cz-Kra IV-21, A-478

Image 2: Binder jacket for the set of parts of the anonymous Ciaccona à 3 cori, credit Archbishop’s Chateau, Kroměříž, Cz-Kra XIV-159, A-870

Image 3: A page of score from the anonymous Ciaccona à 3 cori from the Kroměříž collection. *The image shows how the bass of the string ensemble (5th staff from the top) and of the continuo (bottom staff) differ in the score, though this isn’t reflected in the set of part books, credit Archbishop’s Chateau, Kroměříž, Cz-Kra III-122, A-462