Why the money title?

We puzzled for a while over why Rittler’s 1000-Guilder Sonata, the second work on this program, has such an enigmatic title. Was it composed for a 1000-guilder commission? Is there a melody called “1000 Guilders” that this contains? While both might be possible, the most interesting explanation turns out to be something more whimsical and, coincidentally, apt for our here-and-now.

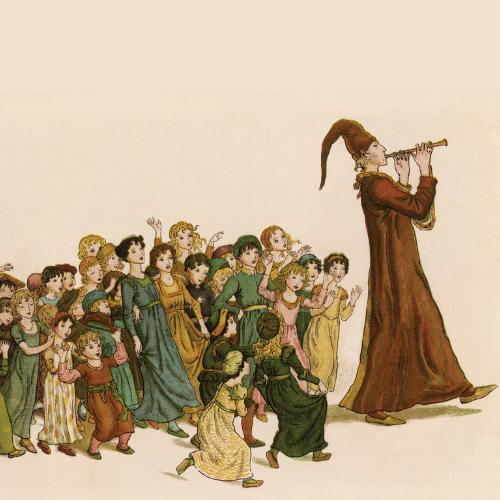

From Central European folklore comes the story about a rat catcher, now popularly known as The Pied Piper of Hamelin thanks to the Brothers Grimm. The tale recalls an historical event, albeit garnished with poetic liberty.

The better-known story goes that in 1284, Hamelin had a bad rat infestation, which a travelling musician—a piper dressed in pied (multicolored) attire—negotiated with the town’s leadership to fix. And fix it he did. He led the rats away by playing his enchanted pipe. When he returned to rat-free Hamelin to collect his fee and the town refused to pay the negotiated amount, he used his charmed music once again, this time to whisk off 130 of the town’s children who, along with the magician-cum-musician, were never seen again.

The fee in dispute? 1000 guilders.

The oldest attested accounts of the incident include the piper and the disappearance of the children, but no rats and no pay dispute. The following comes from a 1585 transcript of a thirteenth-century entry in the Hamelin town record.

“In the year 1284 on the Feast of Saint John and Saint Paul, the 26th day of the month of June, one hundred thirty children born in Hamelin were led by a piper dressed in many colors out of the city and up Mt Koppen near Calvary, taken out through the East Gate, and lost.“

There’s plenty of discussion among historians concerning the how’s, why’s and where’s of the children’s disappearance and the piper’s role in it. The one historians like, because it has the history to back it up, is the so-called Exodus Hamelensis. This occured late in the thirteenth century, when agents for the then-archbishop of Olomouc (OH-loh-mōwts, or Olmütz in German) recruited young inhabitants of Hamelin and other Central European towns to colonize his Moravian archdiocese. The piper in this case symbolizes the well-dressed agents. “Children” can be read as native inhabitants, viz. “Children of Israel”, for instance.

Quite apart from the fanciful musical aspect of the story, which would have spoken to a composer and his audience, the exodus explanation would have special poetic significance for the composer of the 1000-Guilder Sonata, Philipp Jacob Rittler, and for his employer, Prince Karl II von Liechtenstein-Castelcorn, the seventeenth-century bishop of that same archdiocese in Olomouc.

And then the rats appeared

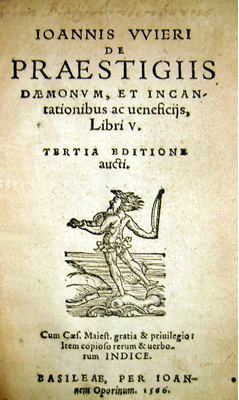

The rats first appear in sixteenth-century accounts, including one of the earliest by Johannes Weier in De Præstigiis Dæmonum (On the Trickery of Demons), 1566, in which he writes:

A certain piper attended to coaxing out Hamelin’s mice, following which the town compensated his deed with ingratitude when they did not satisfy their end of the bargain. And so in the year one thousand two hundred eighty-four, on the twenty-sixth day of June, one hundred and thirty native children of Hamelin followed this so-described “pied” piper (on account of his multicolored garb) and vanished at the place called Calvary beneath Mt Koppen. A remaining survivor told the tale. Take heed of the bloodthirsty demon piper.

This is the version of the story that Rittler would likely have been familiar with, which gets called Krysaři in Czech and Rattenfänger in German.

This is the same vein of the story that Johann Wolfgang von Goethe versified in Der Rattenfänger of 1803. In 1806, Ludwig Achim von Arnim and Clemens Brentano included a 10-strophe song about the pied piper in their 1806 anthology of old German songs, Des Knaben Wunderhorn (the boy’s magical horn). Brothers Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm included the tale in their 1816 Deutsche Sagen (German tales). And in the English-speaking world came Robert Browning’s “The Pied Piper of Hamelin”, which came out in in his Dramatic Lyrics of 1842.

Here is an excerpt of Browning’s telling:

Rats!

They fought the dogs, and killed the cats,

And bit the babies in the cradles,

And eat the cheeses out of the vats,

And licked the soup from the cooks’ own ladles,

Split open the kegs of salted sprats,

Made nests inside men’s Sunday hats,

And even spoiled the women’s chats

By drowning their speaking

With shrieking and squeaking

In fifty different sharps and flats.

Robert Browning, “The Pied Piper of Hamelin”, Dramatic Lyrics, 1842.

The story continued to resonate with composers, never more so than for the nineteenth century Romantic nationalists, who cultivated renewed interest in Central- and Northern European folklore. Various lyrics in Des Knaben Wunderhorn were set as Lieder by Brahms, Schumann and perhaps most famously Gustav Mahler.

As for Rittler’s Thousand-Guilder Sonata, its very structure invites a bit of speculation. “Der Rattenfänger” runs 10 verses as it appears in Des Knaben Wunderhorn. The subtitle of Wunderhorn is “old German songs.” However, the matter of whether Wunderhorn’s “Rattenfänger” is truly traditional lyrics or something composed by Brentano or von Achim remains unsettled. If it’s a confirmed old song, then perhaps Rittler’s structuring of the Thousand Guilder Sonata into 10 sections is a conscious nod to the 10 strophes of the “Rattenfänger” folk song.

Pestilence!

As for those rats, it is fitting that they inserted themselves into the tale starting in the 1500’s, when outbreaks of rat-borne pestilence and the accompanying, terrible death tolls were too common. It’s a theme that audiences today can relate to as we continue to live through a global pandemic. Meanwhile, take the lessons from the tale: music can make your situation better, but keep an eye on your children and never shortchange your musicians.