part 1: our backstage view

The first weekend in April, the Tempesta di Mare Chamber Players will perform the full set of Bach’s six trio sonatas, BWV 525–530. Though these pieces survive as a set of sonatas for solo organ, we’ve recorded and are soon performing them as chamber music. Performances will take place in Wilmington, Center City and Chestnut Hill (click here for more info and to get your tickets).

Note that I said “survive as.” We know that some of this music was also scored as chamber music because isolated chamber music versions survive. Some of the arrangements are Bach’s, while others are by contemporaries known and unknown.

We have taken the fact that this music had contemporary chamber versions as a cue not to reconstruct anything that’s been lost, but rather to reimagine the whole set with orchestrations of our own choosing that cater to our core ensemble of recorder, two violins, cello/viola da gamba, lute and harpsichord.

The beauty of playing this all as chamber music is that six monologues for a solo instrument become dialogues among a cast of distinct characters.

In our version, four of the works remain true to the organ sonatas’ three-voice texture (an organist plays the two trebles parts with the hands on two separate manuals, while the bass part gets played by the feet on a rank of pedals). For the other two sonatas, we allowed ourselves to expand to a four-voice texture by adding a third upper part, so that we could begin and end a performance with the full ensemble. A concert is a show, after all, and shows have opening and closing numbers, with or without a kick line.

I will add that this is my favorite sort of music from Bach because the sonatas are so concise. All the endings come just where you want it to end, neither too abrupt nor too delayed. It’s very baby bear.

To maximize color, we have a different orchestration for each of the sonatas. We’ve also made a point that each of the instruments that normally have a supporting role, i.e. the continuo instruments, get to play one of the upper melodies at some point in the cycle. All orchestrations are found elsewhere in originals by Bach or his contemporaries in other music.

How bach transformed his own content

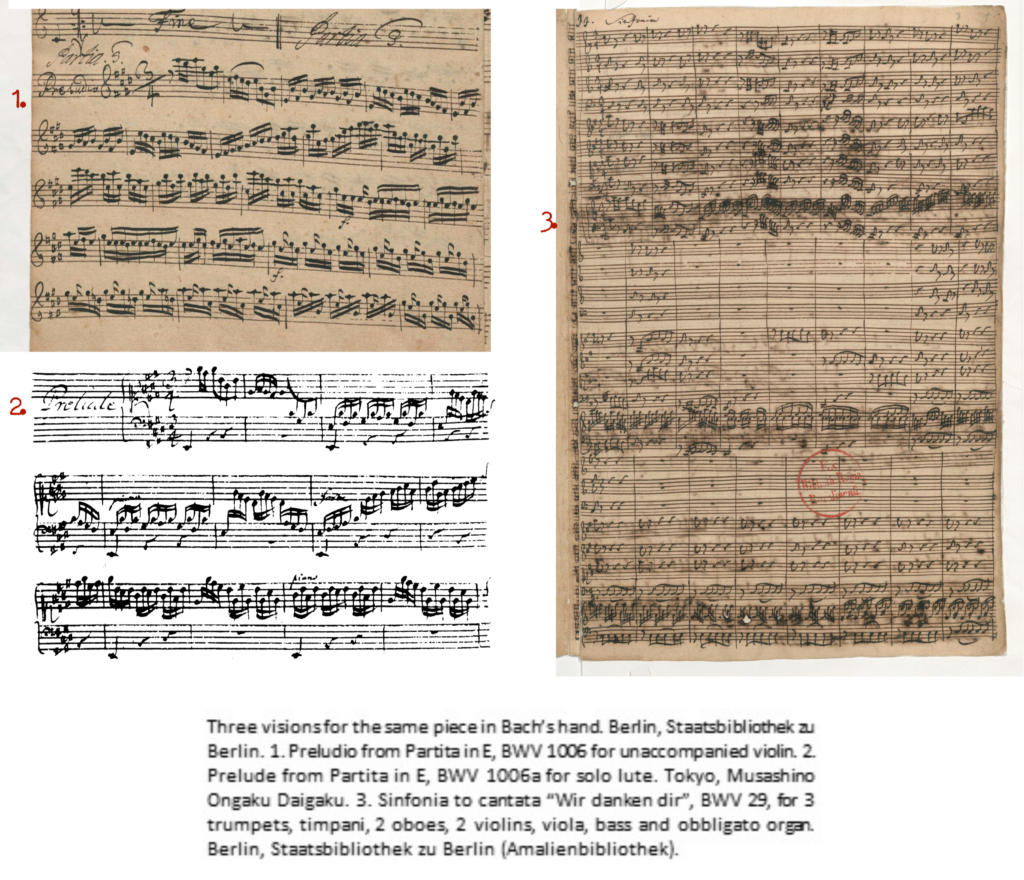

Here’s a well-known piece that makes a great example of how Bach transforms content when he recycles his own ideas. This example is pretty famous, and it’s sufficiently permeated popular culture that anyone who now comes to classical music concerts has likely heard it.

If you love unaccompanied violin music, you’ll have heard it as the first movement of the violin partita, BWV 1006. If you are a guitar-and-lute fan, you’ve come across its cousin, the lute suite, BWV 1006a. If you are a cantatas maven, you know this as the sinfonia to Cantata 29. Or, if like me, your introduction to baroque music was Walter Carlos’s Switched on Bach, you know it as the track from that album based on that sinfonia. You can compare these three versions here:

1. Bach: Preludio from Partita in E, BWV 1006 for unaccompanied violin. ShunsukeSatō.

2. Bach: Prelude from Partita in E, BWV 1006a for solo lute. Evangelina Mascardi.

3. Bach: Sinfonia to cantata “Wir danken dir”, BWV 29, for 3 trumpets, timpani, 2 oboes,2 violins, viola, bass and obbligato organ. Nederlandse Bachvereniging.

What’s interesting to observe is the distinct flavor of each texture: the leanness of a lone violin; the extra richness of the same music with the lute’s added bass line; the fanfare of that same melody once more played on an organ against a full orchestra.

We’ll talk about the individual sonatas in the next installment of this blog series.