Maybe he thought he could make it easy.

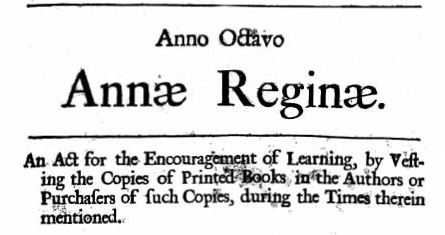

In 1777, when Lord Marshall, Lord Chief Justice of the King’s Bench, ruled that protections should be extended to music under 1710’s Statute of Anne—the first copyright law in the English-speaking world—he included the definition: “Music is a science, it may be written; and the mode of conveying the ideas, is by signs and marks….”

Let’s Get it on

Lawyers and litigants have been worrying that definition like a puppy with a toy ever since.

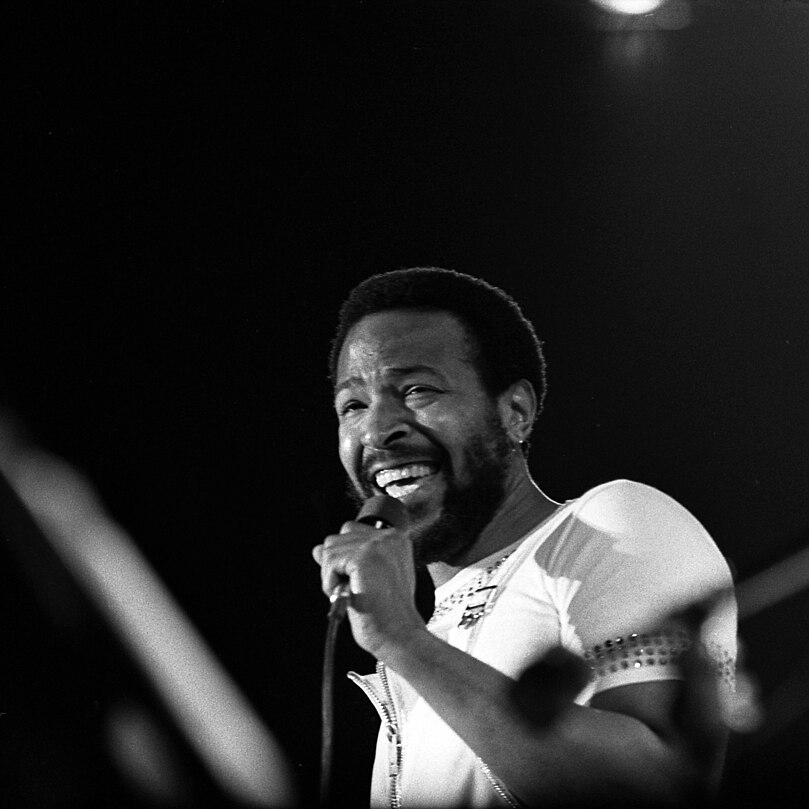

In 2017, the estate and heirs of musician Ed Townsend took English singer-songwriter Ed Sheeran to court. In 1972, Townsend co-wrote the soul classic “Let’s Get It On” with Motown legend Marvin Gaye (Townsend passed away in 2003, Gaye in 1984). Townsend’s descendants claimed that Sheeran plagiarized “Let’s Get It On” while writing his song, “Thinking Out Loud,” in 2014.

This was big league. Gaye and Sheeran are giants of popular music. And Griffin et al v Sheeran et al had a conundrum at its heart, one faced by generations of litigants and soon by a Manhattan jury: what exactly makes “Let’s Get It On” Gaye-y and “Thinking Out Loud” Sheeran-y? How much difference between them counts as difference enough? Where do you draw the line? And how?

300 years prior, another Englishman, George Frideric Handel—born in Germany but naturalized in 1727—was also accused of sampling his contemporaries’ work.

Stolen, Not Stolen, and Somewhere in Between

It was nothing new in the baroque, actually. Almost all baroque composers borrowed. They borrowed from themselves, reusing tunes or passages or even entire movements from earlier pieces and reworking them into something new. They borrowed from their colleagues—not necessarily with acknowledgement or consent, but it happened. Handel was just one of the biggest practitioners (or malefactors, depending on how you look at it).

His habits were well known and he got called out on them. When some new Italian opera scores arrived in London in 1743, for instance, his friend and librettist Charles Jennens (Messiah) immediately wrote an acquaintance, “I dare say I shall catch him stealing from them….”

Handel wasn’t sued. He couldn’t have been, as the Lord Chief Justice’s ruling came a full twenty years after his death. Posterity came down on him hard, though. Through the 19th-century and some of the 20th, his borrowing got bad posthumous press. It didn’t fit into the romantic era’s ethos of solitary individualism. And there was so much of it (and some of it—not all, but a small portion—is admittedly theft).

It hasn’t been until the early music revival that more people started to treat Handel’s magpie habits with the kind of respect due his enormous talent and contributions to music. Scholars and musicians are looking beyond the occasional pilferage to look closely at what he borrowed and transformed, the line between where something is someone else and where it’s become Handel. It’s an endeavor that has consequences beyond Handel.

Right to a jury

Griffin et al v Sheeran et al came to trial in 2023. The Townsend family’s filing described similarities of “Thinking Out Loud” to “Let’s Get It On” in terms of “harmonic, melodic and rhythmic compositions.” Lawyers on both sides piled up evidence. Music scholars, including at least one who specializes in plagiarism cases—a “forensic musicologist”—testified. Regular citizens were called in to provide their unschooled reactions to the two songs. Ed Sheeran took the stand with guitar in hand and sang and played the jury through his process of composing “Thinking Out Loud.”

The conclusion was in no way foregone. Music copyright infringement suits are coming fast and thick and they go either way, case by case. The memory of the 1976 verdict against George Harrison (Bright Tunes Music v Harrisongs Music) is still alive—and chilling. In that case, the jury found that the former Beatle in writing “My Sweet Lord” in 1970 misappropriated the song “He’s So Fine,” recorded by the Chiffons in 1963—albeit unconsciously. Unconscious or not, Harrison paid a big settlement.

When Griffin v Sheeran went to the jurors, though, they found for Sheeran. It took them only two-and-a-half hours. Case closed.

THE AURAL SOUP THAT FLOWS NONSTOP

But there are and will be more. So many creators like Handel, Harrison and Sheeran do indeed seem to take their inspirations not out of thin air, but out of the aural soup that flows nonstop in the sensory environment. They’ll take a tune or a bassline, sure, but they’ll give it new life as their own. Where they infringe, that’s call by call. It’s not easy. Pace Lord Marshall, music isn’t a science.

Handel’s friend and frequent critic Johann Mattheson had his take on music’s magpies. In the 1720’s, in his periodical Critica Musica, he wrote that getting your work stolen can be good as long as the thief does something good with it. The original creator “…gains an immense honor if every now and then, a great man comes across their work and, as it were, borrows its gist. If only three people know that the idea was originally yours, it’s honor enough!”

Sheeran’s lawyers had their take, too. After the verdict, in 2023, they wrote:

“This verdict is a massive win for all songwriters out there who now will not be forced to hesitate about using basic elements of their toolkit …. Everyone benefits from artists being able to use these elements to create new music for all of us to enjoy.”

Case by case.

Notes:

William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield, Bach v Longman (1777) 2 Cowp. 623. Yes, it’s J. S. Bach’s youngest son, John Christian. When J. C. Bach and his producing partner, Karl Friedrich Abel, discovered that their publisher was selling bootlegs, they didn’t get mad, they got even.

Johann Mattheson, Critica Musica 1:72, “wohl aber eine ungemeine Ehre zuwächst/wenn ein berühmter Mann ihm dann und wann auf die Spuhr geräth/und gleichsam seiner Gedanken wahren Grund von ihm borget. Soltens auch nur drey Wissen/so is es schon Ehre genug!”

Translation author.

Pryor Cashman press release, “Pryor Cashman Client Ed Sheeran Wins Landmark Copyright Case Over ‘Thinking Out Loud,’” May 4, 2023.

Anne Schuster Hunter is a writer and art historian living in Philadelphia, www.anneschusterhunter.com.