How Tempesta di Mare discovered Georg Reutter

It was, almost literally, a magic moment.

One fine evening in June 2017, on a two-block walk through Philadelphia’s Rittenhouse Square, Richard Stone, Tempesta di Mare’s artistic co-director, stumbled on something new, exciting, and captivating. That was the moment he became aware of the music of Georg Reutter—now the focus of Tempesta di Mare’s next season-long, full-force immersion.

It was totally unexpected. As Richard told the story over a recent Zoom call, he and the Tempesta players had just wrapped a session recording the group’s Janitsch cd (Chandos, 2018). Everything had gone splendidly and the gang was heading out to celebrate. A friend-of-a-friend was coming along. On the way over, he handed Richard a pair of earbuds. “You’ve got to hear this music,” he said.

A bootleg recording through Walkman Earbuds

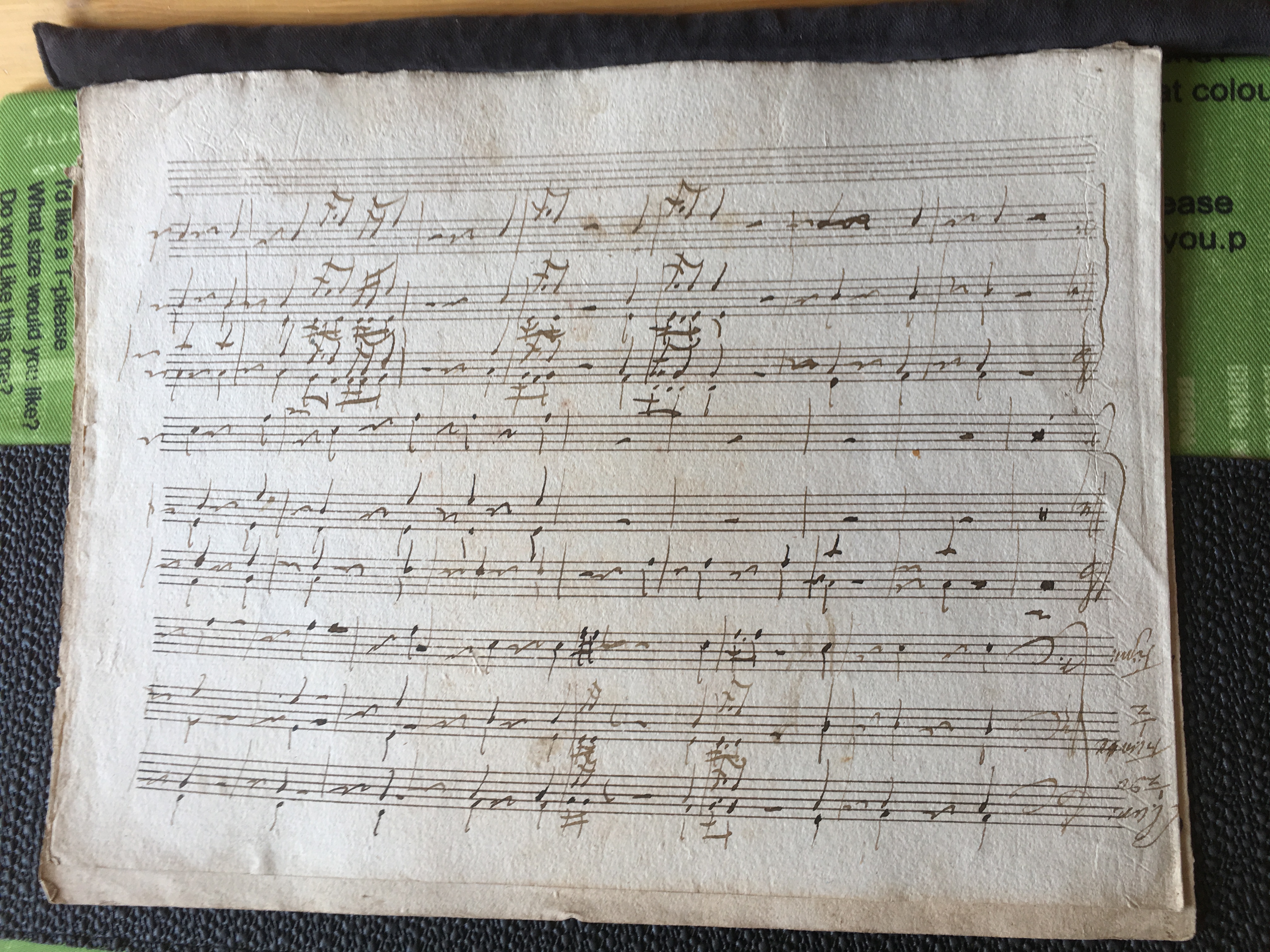

Stone found himself listening to a recording ripped from an old 1970 Vox/Turnabout vinyl disc. It was the Mainz Chamber Orchestra on an album called A Gala Dinner Concert at the Court of Vienna and—to add to the odd romance of the moment—was coming from a tape cassette in a classic, vintage Sony Walkman. The friend-of-the-friend (an audio producer, hence the enviable audio collectables) recommended just one track to Richard. It was titled “Servizio di Tavola” and it was by Reutter.

“Even with ‘70’s-era, thoroughly ‘modern’ performance practice, the music came through loud and clear,” said Richard. “It had four trumpets and timpani, woodwinds and strings and it was so much fun. The music was spectacular. Such a shiny thing!”

From that moment, Richard was all in.

Bernardo Bellotto, View of Vienna from Belvedere, 1758-1761; Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. Wikimedia Commons

A year later, with research grants in hand from the Pew Center for Arts & Heritage and The Peabody Institute of Johns Hopkins University, Richard was in Vienna discovering as much Reutter as he could. He spent two weeks in the archives of the Austrian National Library, the Society of Friends of Music, and the Cistercian monastery of Heiligenkreuz Abbey in the Vienna Woods—the three major repositories of Reutter’s work. The more Reutter that Richard found, the more he liked it.

“It’s Viennese”

He was discovering, Richard said, a whole new flavor of European high baroque. He described how different it felt as soon as he started looking into it. “The thing that I learned very quickly is that it’s not German music or Italian or French. It’s Viennese. It’s its own thing.”

And it’s something that’s new and different to most present-day audiences. We probably haven’t heard a lot of Viennese high baroque (from about 1710 through the 1750’s). Even now, when interest in baroque music in general is so high, it’s one area that doesn’t get much play. It’s as if at some point, music history decided it could just skip over 18th-century Vienna until 1760 and the glory years of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. That old Vox/Turnabout Gala Dinner recording that found Richard on a fine June night is a miraculous anomaly.

Our loss, according to Richard. Viennese mid-18th-century baroque is very fine indeed. It’s full of the soaring Italianate melodies and touches of French elegance that provided so much wonderful music in all the European capitals at the time.

But Vienna’s international galant adds a flavor of its own to the style. “It’s counterpoint. What else would it be?” Richard said. Counterpoint , it seems, is as quintessentially Viennese as waltzes and Kaffee mit Schlag. The old polyphonic tradition may have ebbed elsewhere, but not in Habsburg Vienna. It flourished not just in the renaissance but also under baroque-era Habsburg emperors who never ceased to love it (Leopold I, Joseph I, Charles VI, and even Maria Theresa, a little). Those old-style intertwined voices and glowing sonorities provided a sonic bedrock right up through Viennese composers of Reutter’s generation.

A three year preoccupation – and counting

Richard finds it deeply attractive. For almost three years now, Reutter has become a major preoccupation for him. He’s been continuing to research, preparing scores, planning projects—and having to stand by while they were sidelined during the pandemic shutdown. He can’t wait to get going now.

Tempesta di Mare is known for its “deep dives” into a single artist or type of music. They explored, for instance, Johann Friedrich Fasch in 2007-2010, French orchestral music in 2014-15 and Telemann in 2017. Next season, Reutter is going to be Tempesta’s new best thing, with a year-long, in-depth look during 2021-22.

“We’ll all discover this together as an orchestra,” Richard said. “What is there? We know we like it, but let’s really go in deep. What is it about this music that makes it so special?”

“And all,” said Richard, “because somebody played me an obscure old recording while we were walking down the street.”

Magic.

Anne Schuster Hunter is a writer, teacher of creative writing, and art historian in Philadelphia. www.anneschusterhunter.com

Many thanks to Paul Westcott, our now legendary friend-of-a-friend!