Tempesta di Mare presents Anonymous.

For something that’s nothing, “anonymous” sure carries a lot of baggage.

Literally “without a name,” “anonymous” would seem to be value-neutral. It gets into some shady business, though. “Anonymous tip,” “anonymous letter,” “anonymous source”? Secretive! Suspicious! “An anonymous face in the crowd”? Bleak! Names are important in our society. Not having one is a problem.

No name = shady business

That’s certainly true in the arts. In the arts, a maker’s name and reputation validates a work. When a 17th-century painting formerly attributed to Rembrandt gets reattributed to “School of Rembrandt,” it loses value in the art market and in public perception, too. Right now the Vermeer Girl with a Flute at the National Gallery has started on a reattribution journey from Vermeer to being a not-Vermeer. I should know better, but I find myself looking at the reproduction of a painting I love and thinking, “hmmmm, that brushwork actually is a little clumsy, isn’t it?”

In the field of early music an anonymous manuscript is, almost literally, at the bottom of the pile.

Finding unsigned treasures in Kroměříž

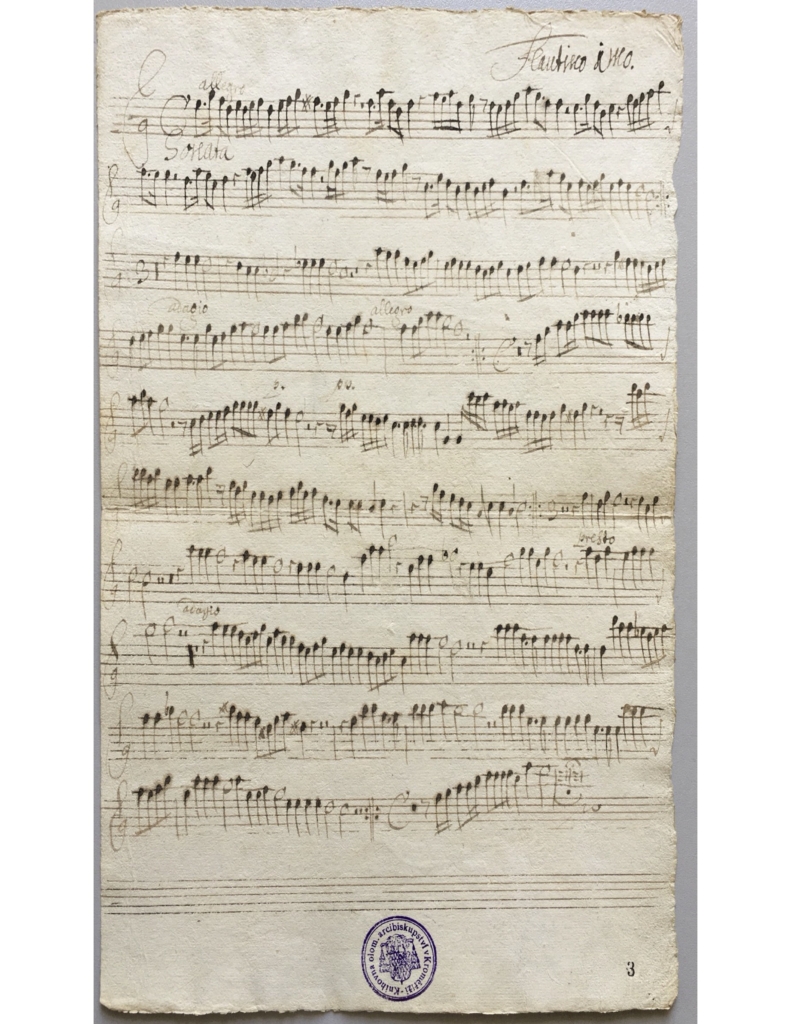

That is a crying shame, according to Richard Stone, artistic co-director of Tempesta. In the musical archive in the town of Kroměříž, Czech Republic, which he visited in 2019, the works-without-name were some of the most exciting music he’s seen in years. Tempesta di Mare is proudly presenting 11 of them—without a name in the bunch—in the upcoming concert, Anonymous.

In fact, it was the hunt for a known, named quantity—17th-century Austrian composer Philipp Jakob Rittler—that originally took him to Kroměříž. While looking through manuscripts in the archive, though, he noticed chamber pieces for wind and strings that perfectly fit Tempesta’s instrumentation, wind and strings. Being anonymous, they had been overlooked for centuries. “What is this stuff?” Richard thought. “Is it any good?” He got his answer when the group transcribed a few and played them in the 2019 Czech Christmas show. The anonymouses brought down the house.

These are a few of my favorite things

There are plenty more. Strangely, almost 40% of the 17th-century music at Kroměříž are anonymous, almost 1,150 pieces. It’s a mystery why—perhaps some oddity in the Kroměříž orchestra performance culture and library organization allowed the names to be lost. Notwithstanding, the finds from Kroměříž are among Tempesta’s new favorite things. “Every piece on the Anonymous program is my favorite child,” says Richard, happily.

Bringing these anonymous works back to life is something Richard and Gwyn Roberts, Tempesta’s other co-founder and co-artistic director, find uniquely satisfying. They are always suspicious of “Great Man” theories, with their 19th-century biases toward homogeneous culture and elitism. Their inclusive view of the past, “history from below,” that considers environments, colleagues, networks, patrons and audiences of a period to be as interesting as its silverbacks. They’re leaping at the chance to rediscover and share some of what made Kroměříž such a hub of intense musical activity; it opens new vistas for them, certainly, and they hope provides a deeper understanding—and pleasure!—for their players and audiences.

Along the way, they’re discovering great people—even if those people don’t have names.

It was impossible not to add this addendum:

Does a rose by any other name smell as sweet, even if that name is “anonymous”?

In 2007, violin superstar Joshua Bell and The Washington Post teamed up for a famous prank. Bell busked in a D.C. metro station one January morning during rush hour completely anonymously. He was dressed in a tee shirt and ball cap to look like any other kid playing in the subway (he was 39 in 2007, but looked young) and was without retinue or camera people or any kind of identification at all. Even his Stradivarius was incognito. He played for 43 minutes and played terrific material, too, including the famously knotty chaconne from Bach’s Partita No. 2 in d, which he played twice through.

Joshua Bell routinely fills big halls. But that morning in the Metro, in the morning rush, with nothing but their ears to tell them what was going on, hardly anybody stopped to listen—and hardly anybody left a tip. He only got $32.17 in his open case, and $20 of that was from somebody who recognized him.

Those people running off to work missed him. They missed out, too, because he sounded great (the Post put footage up from the Metro’s security camera here, https://youtu.be/hnOPu0_YWhw). Yes, names matter. The Bell/Post gag certainly makes that point. But it also, like Tempesta, is a good reminder to us to stop and smell the roses—even the ones with no name.

That Joshua Bell story went viral and has been retold in many versions. For the original, which is a fantastic read, see Gene Weingarten, “Pearls Before Breakfast: Can one of the nation’s great musicians cut through the fog of a D. C. rush hour? Let’s find out,” The Washington Post Magazine, April 8, 2007, http://wapo.st/1riCfjT?tid=ss_mail.

Anne Schuster Hunter is a writer and art historian living in Philadelphia, www.anneschusterhunter.com.