You know Vivaldi’s Spring from The Four Seasons. Everybody knows Spring from The Four Seasons. Even if they don’t think they know Spring, they do. Everybody recognizes that wonderful, lilting opening theme.

Remember when Spring had a big moment as a ringtone? You’d hear it piping out of pockets on the grey, grimy subway platform and for a moment, your heart would lift, the Broad Street Line transformed into verdant grove, a safe, welcoming, gentle space populated by lovely, happy people, with birds in the branches and bees flitting through the undergrowth.

Yes, every time we hear it, Spring seems eternally fresh, forever new.

Yes, every time we hear it, Spring seems eternally fresh, forever new. It’s an amazing achievement. In fact, though, Spring was very much of its time.

It’s not just the nature sounds that Vivaldi builds into this wonderful piece of music. Violins tweeting birdsong and burbling like brooks—that’s old. Mimesis in music goes back centuries before the baroque, although Vivaldi delivers it superbly.

It’s Spring itself that’s old. Vivaldi draws on an ancient trope in Western culture when he gives us Spring’s dewy, fresh, vivid, unspoiled nature. It’s a vision of Arcadia, an imaginary land from ancient time. Appearing in literature, music and art at least back to the Romans, Arcadia is a fantasy land with blue skies, rolling hills, no modern excrescences, and beautiful, simple rustics with nothing but love and happiness on their minds. It’s the world in its perfect, new state—before modern people messed it up.

Arcadia was huge in the 17th‐ and 18th centuries. It was a thing. Baroque artists returned to Arcadia again and again, producing myriads of shepherds and shepherdesses—or elegant ladies and gentleman looking like shepherds and shepherdesses—enjoying themselves over and over in bucolic splendor.

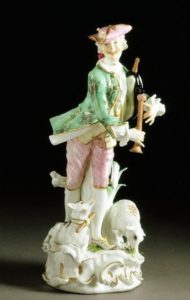

Arcadia—or its influence—turns up in paintings, prints, operas, design, cuisine, gardens and all those painfully twee ceramic shepherds, shepherdesses and cutesy-poo little lambkins that the 18th century loved and that for many of us remain a baffling aspect of baroque culture.

Those Meissen figurines are hard to relate to now. When you look at them, the concept of Arcadia seems out of reach, lost in the past. But Arcadia didn’t die out. China shepherdesses didn’t even die out—in America, they came back like gangbusters after 1945 as Hummel figures. And that fantasy of untrammeled naturalness, Arcadia, is very much with us still, almost as strong now as in the 18th.

Think about it. Farm-to-table. Etsy. Community gardening. We’re sad when reality falls short of Arcadia; you can hear that air of wistfulness in Spring. But it’s an ideal that keeps us going.

Perhaps Arcadia is wish-fulfillment when life seems out of balance. In the 17th‐ and 18th centuries, Europe was changing at a breathtaking pace. Trade surged, wealth exploded. European population skyrocketed and rural people inundated the cities. Cities became more urban by the hour with paving, streetlights, massive buildings, nasty alleys, and questionable sanitary arrangements. No wonder the 18th century longed for swaying branches and babbling brooks.

Is it any wonder that Vivaldi’s Spring speaks so loudly to us now? He wrote it in the 1700’s. It offered a balm to the modern soul then.

It still does.

Anne Schuster Hunter is a writer and art historian in Philadelphia, www.anneschusterhunter.com. She teaches creative writing at Temple University Center City. Valuable assistance to this essay was provided by Emma Haviland-Blunk and Rachel Hottle through the Swarthmore College Extern Program. Many thanks to Molly Hemphill.

Images:

Antoine Watteau, “L’Embarquement pour Cythere”, 1717. Paris, Louvre.

Wikimedia Commons

The figure, about 1750. Meissen porcelain factory. London, Victoria, and Albert Museum.

Wikimedia Commons