It was a pamphlet that went out to the London public immediately after a performance of Bononcini’s Astianatte at King’s Theatre in 1727 describing an onstage fight between the opera’s leading ladies:

A most horrid battle

“The DEVIL to pay at St. JAMES’s: Or A full and true ACCOUNT of a most horrid BATTLE between Madam FAUSTINA and Madam CUZZONI…”

Seems familiar doesn’t it? All that p. r. churn, all the Drake vs. Kendrick. The incident almost certainly never happened, or at least not like that—the opera stars in question had known each other for years and continued to perform together peaceably for decades following.

Hooligans!

The audiences were pretty wild, though. The 1720’s London opera season elicited present-day British football-level passion from the fans. Operas became endurance events for music-lovers, with the partisans determined to drown out the soloists and each other depending on which diva was trying to hold the floor.

That’s how much the baroque public loved their opera stars.

Tempesta di Mare puts two of those stars, that very same Faustina (Faustina Bordoni Hasse) and Santina (Tasca), back in the spotlight with Faustina and Santina. After all, it’s where they belong.

Glimmering Stage Confections

And to realize the scale of their achievements, appreciate how very big opera and particularly Italian opera was in the late 17th– and early 18th-centuries. Opera productions ruled big cities, little cities, wannabe cities everywhere, delighting those who could afford or beg tickets and providing exciting buzz for everybody else. Productions were glittering stage confections with shimmering sets, magical stage effects, gorgeous music—and fabulous singers. And Faustina and Santina were two of the brightest stars in the opera firmament.

We don’t know so much about Santina now, other than an her almost unbelievable rags-to-riches origin story—she was one of the abandoned babies who was deposited at one of Venice’s charity hospitals, the famous Ospedale della Pietà, and went on in adulthood to enter opera’s highest ranks.

Legendary Faustina Bordoni

But we know a lot about Faustina. As one of the most famous opera stars of the era, she pushed the top tiers of stardom to a whole new level. Also born in Venice, but with a conventional background, Faustina started touring in her teens and by her twenties was an international star who earned “astronomical” fees when, for instance, she premiered in Handel’s Alessandro in London at age 29. She toured everywhere: Naples, more London, Parma, lots of Vienna, lots more Dresden (particularly after marriage to composer J. A. Hasse, Oberkapellmeister to Dresden’s famed Hofkapelle) and so on for decades—all on unpaved roads in stagecoaches with leather strap suspensions. They were giants in those days.

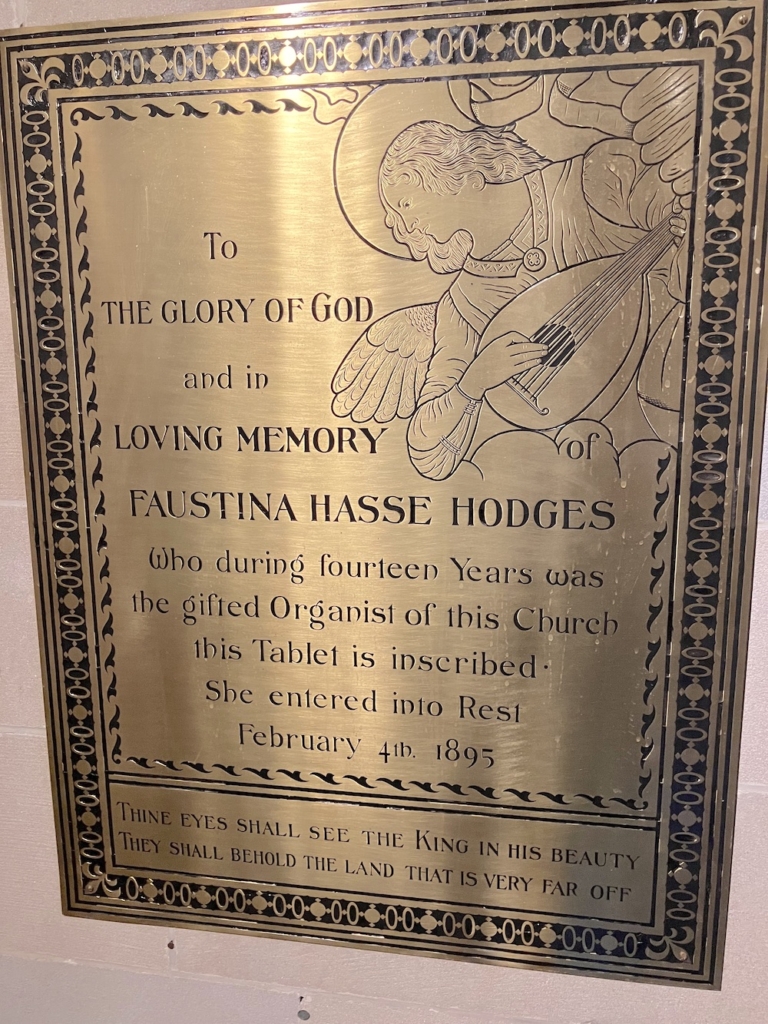

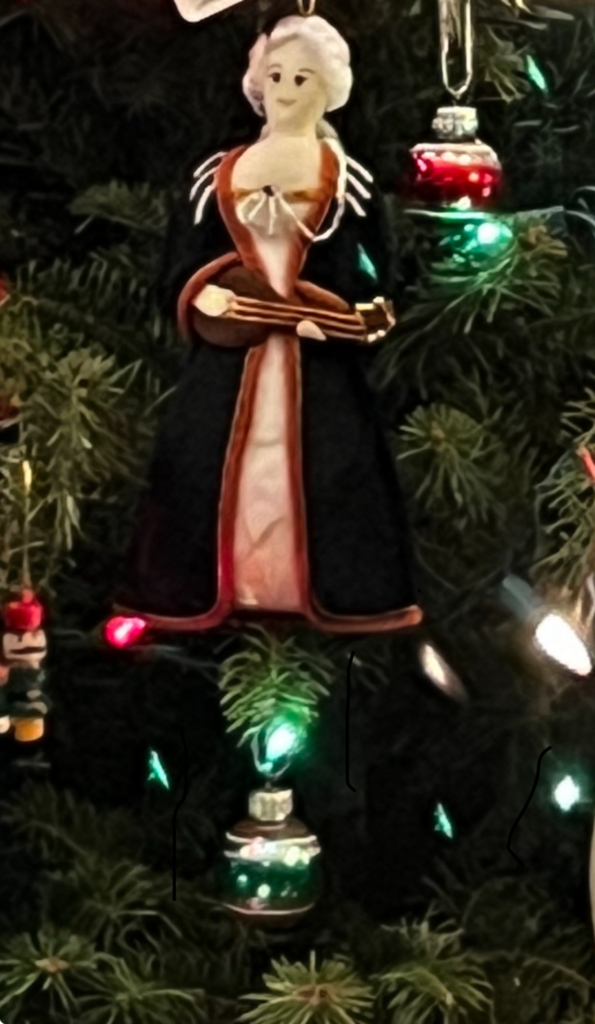

We actually have an indirect homage to Faustina right here in Philadelphia: a plaque in St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Chestnut Hill honoring Faustina Hasse Hodges, a 19th-century composer and organist (and Philadelphia transplant) who was no doubt proud to bear such an illustrious name. And as a Christmas ornament.

Fame, it seems, really can live forever.

Fabulous Gabriela Estephanie Solís

In Tempesta’s program, mezzo-soprano Gabriela Estephanie Solís—fabulous in her own right—will perform arias Faustina sang in the 1720s. I caught up with Solís on Zoom to find out how she feels about taking on the legendary Bordoni. But first, how about that Faustina “TMZ moment”?

“Oh, it’s very funny. I find it very funny,” said Solís. “It’s interesting to think that we as humans have been doing the same sensationalizing for centuries. So many things have changed, but so many things are the same.”

It has a serious aspect too, though, Solís continued.

18th-century Labelling

“You know, press everywhere loves feeding into reinforcing these negative stereotypes about women, particularly women who have the assertiveness to be on stage and present confidence. They get labelled as difficult, stigmatized. This is not a new phenomenon! But when you think about this time period, around 1700, not that long before then, women were not allowed to sing in public. There’ s still the shadow of that memory in the early 18th century. Someone like Faustina on stage singing confidently was very threatening to a lot of people, I’m sure.”

So how does a singer like Solís keep that boundary in mind when she’s singing this repertoire. How does she negotiate straddling the world Faustina lived in and ours? How, for instance, does a singer like Solís negotiate all the elaborate ornamentation baroque composers expected opera singers to add to their music? This was Faustina’s particular strengths, according to commentators. Solís said:

“In early music, you have to come to the music with the mindset of a co-composer. Before you get into the technicalities of which ornamentation to do, or whether you’re doing the trill above the note or on the note and so on, you have to take on the confident mindset that these singers would have had, that Faustina would have had, this person who was immersed in the language.

Faustina would not have stood for it

“Faustina would have been so fluent and so confident about it! I’m sure no conductor would’ve told Faustina, ‘well, actually, I think you should do this ornament this way.’ I’d like to think that she would not have stood for that. She would have said, ‘no, this is the ornament I am doing. This is what I’m bringing as an artist.’

And that’s what Solís wants to bring too. She clearly admires that confidence, that presence that her forbear brought.

“As a performer,” says Gabriela Estephanie Solís, “I am co-creating music. The composer has given me this beautiful structure and now I am coming in as an artist, making a significant contribution.”

Faustina Bordoni lived until 1781, age 84, gathering plaudits and even more fame all along the way. She was lived to witness the dawn of a new era. Mozart visited her in Venice after she’d retired there.

A significant contribution indeed.

Anne Schuster Hunter is a writer and art historian living in Philadelphia, www.anneschusterhunter.com.

Additional Images:

Fox and Faustina Bordoni, J. J. Kändler (Meissen Manufactory), c. 1743 | Metropolitan Museum of Art. Wikimedia Commons

Le Triomphe du goût moderne, Dedié Alla Signora Faustina Bordoni, Caricatures et dessins humoristiques Scènes parodiques — 1701-1788 | Bibliothèque nationale de France. Wikimedia Commons

Plaque in the vestibule at St. Paul’s Church, Chestnut Hill, Philadelphia. Photo: Tempesta di Mare

Christmas Tree ornament of Faustina Bordoni Hasse. Photo: Jamie Png