The six trio sonatas by J. S. Bach BWV 525-530, are special—famously so. “One can’t say enough about their beauty,” wrote Johann Nikolaus Forkel, Bach’s first biographer, as early as 1802.

“They’re little masterpieces, compact and vibrant.”- Tempesta di Mare Co-Director Gwyn Roberts

Tempesta’s audiences agree. The Bach trio sonatas have been Tempesta fan favorites since their premiere and release of their recording on Chandos Records in 2014. And for good reason. Not only are Tempesta’s Bach trios the composer at his happiest, but they’re Bach in the hands of players who are clearly in their element and having a great time. It’s as if the Bach trios were made to be played by Tempesta.

Which is not far from the truth, actually. In some ways, they were.

Something New & Special

It was when Gwyn and Co-Director Richard Stone were preparing for Tempesta’s 10th anniversary season in 2011-’12 that their version of the Bach trios really took root for them. Gwyn and Richard were pondering how best to showcase their group at a watershed: after a decade together of intensive performing, their ensemble was honed to a fine point. The Co-Directors wanted something new and spectacular and perfect for Tempesta to play. Something like the famously special Bach trios.

Notwithstanding that technically, they didn’t exist. Not as chamber music, anyhow.

It’s true. The Bach trios that come down to us through history as unequivocally Bach are not chamber music. They’re organ music (which is why they’re usually called the Bach Organ Trios). But over the centuries, other players—including Gwyn and Richard—have been sure that multi-instrumental music lurked at their core.

A new temptation

For Richard Stone in particular, winnowing it out as a worthy showpiece for their chamber players wasn’t a problem. It was a temptation.

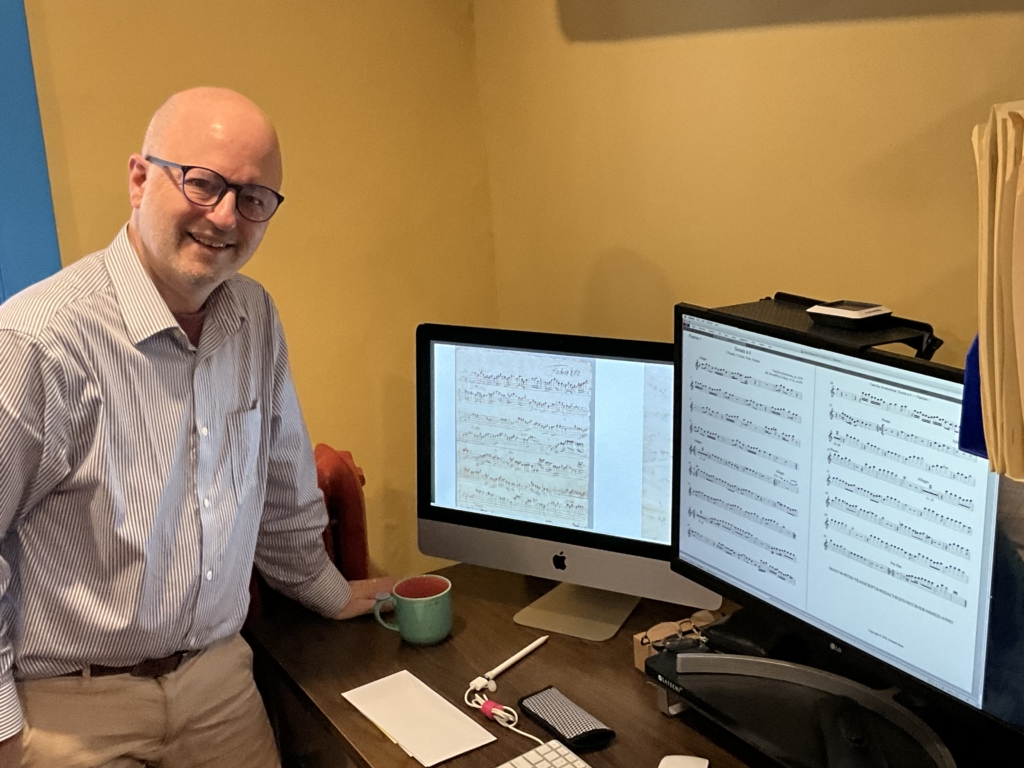

One of Tempesta’s secret strengths is Richard’s remarkable ability to make reconstructions and historically-informed arrangements from often-tattered and sometimes near-invisible remnants of the past. Gwyn has credited his skills as being key to much of Tempesta’s work. “It’s a real driving engine in what we do,” she said. Richard and Gwyn have spent innumerable hours poring through microfiche, microfilm, music databases and centuries-old remnants from which Richard reconstructs lost parts and decrypts fragments, bringing musical riches back from the brink of extinction.

Which Richard proceeded to do for Bach.

the puzzle

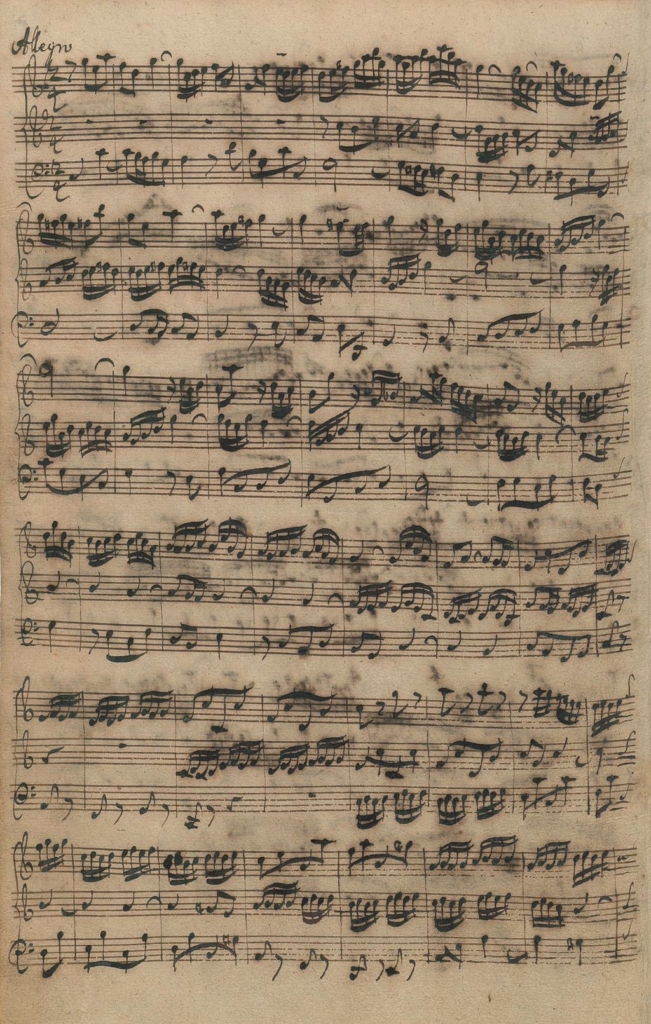

Here’s the puzzle. The trio sonatas are authentic, for sure. They came down as a manuscript in Bach’s own handwriting. Sometime in the late 1720’s, he wrote them all out on two top lines and a bottom line (no figures). Although there’s no title page or directives in his hand these were clearly intended in this instance to be played on an organ with two manuals and a pedalboard. But historically, they’re anomalous. Organ trios as a genre themselves were extremely rare at that—or any—time. Bach’s may be the first of a very small field.

Autograph manuscript of first page of third movement of Bach organ sonata 5, BWV 529,

Bach digital archive, Leipzig

And it’s also clear that the trio sonatas were, in fact, themselves adaptations. Bach borrowed from himself extensively in constructing them. Scholars have been at work identifying where they came from. Many are traceable to other Bach’s organ works but some also came from chamber works for string or winds and continuo. It will probably be impossible to track all the sources down ultimately because, sadly, so much Bach instrumental music has been lost over time. But people continue to try.

but why the organ?

Also lost is the reason why Bach chose to pull them together and make them into such a nice, neat package for organ players. Maybe they were a treat for someone, perhaps, to play for home entertainment on then-fashionable parlor organs? They would have to have been very skilled players—on organ, the trios are fiendishly difficult. Maybe a learning tool for advanced organ students?

German Chamber Organ, 18th century (Franz Casppar Hofer, painter, active 1758) No pedalboard; pedal parts might be played on a bass instrument like a cello Metropolitan Museum of Art

We may never know. But for people like Richard Stone, that very indeterminacy is part of the attraction. The organ sonatas resemble shadows on the wall offering tantalizing clues of the works they once were or could have been begging to be heard. Over the years, many people answered, adapting them to other instruments get wider access to these little gems. As early as 1809 there’s a duo piano version.

tempesta’s reimaginations

With his people in mind, Richard went to work in 2007, re-arranging the six keyboard pieces into mixed-instrument trios, the standard form for baroque-era multi-instrumental chamber music known as trio sonatas (two, three or four top lines over a bass). Gwyn and he settled on their own—and very Tempesta—moods and soundscapes for each: #1 sprightly on alto recorder, violin, cello and harpsichord; #2 dashing and florid on two violins, cello and lute; #3 heartfelt on voice flute, viola da gamba, lute and harpsichord; #4 a somber and ruminative Toccata and Fugue on lute and harpsichord for the Toccata and Fugue; and so on.

Richard Stone and his reconstruction setup, 2023

Photo: Anne Schuster Hunter

Thanks to these new arrangements—or reimaginations, as Stone puts them—we have a chance to hear the trios in a new/old form. It’s meaningful. When the sonatas are played by a group of instrumentalists instead of a single person, it’s a change but also an enhancement. In Tempesta’s hands, it’s as if the result is Bach but more so. That sense of conversation and call-and-response that Bach put in the keyboard version is all the more palpable when actual people are bouncing music off each other in real time and space.

No wonder that the Bach sonatas have become something of a calling card for Tempesta. They identify Tempesta as the special group they are.

And no wonder we love them so.

Anne Schuster Hunter is a writer and art historian living in Philadelphia, www.anneschusterhunter.com.