Imagine Bach and Handel in their music rooms in Leipzig and London, sitting down, opening the fresh, clean pages of music straight off the press, and playing something new they’d just received from their good friend Georg Philipp Telemann. It’s a goosebumpy image, like in the movies when all the superheroes know each other and hang out together.

One of Tempesta di Mare’s ever original shows, The Faithful Music Master, featured music by Telemann owned by his fellow eminent composers and friends Christoph Graupner, J.G. Pisendel, J.S. Bach, and G.F. Handel. Telemann’s music spread far and wide from his home base in Hamburg, Germany, into the collections and homes of his colleagues and a growing community of international music lovers.

It hadn’t been long since musicians were considered only slightly higher than servants in the social hierarchy. But that was changing fast in the 18th-century, and Telemann was at the forefront. This generation of musicians was exploring new career possibilities, independent of town or court. Publishing and distribution would be key, and while all of the composers published a little, Telemann published more. He absolutely self-published more than any other composer, with no middlemen.

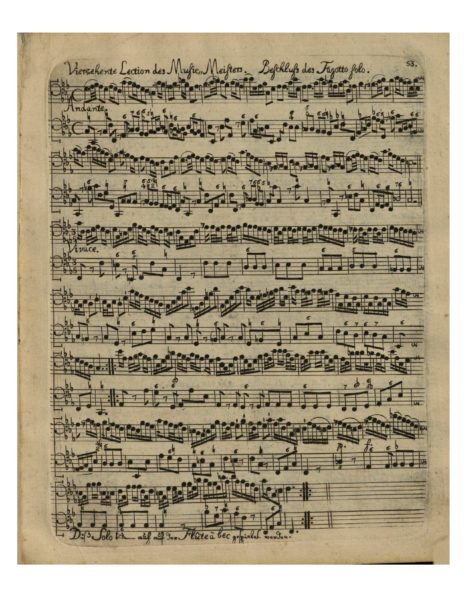

Telemann devoted major efforts to publishing for much of his long life. In his thirties, soon after moving to Hamburg, he launched an entire one-person self-publishing operation. He did it all. He engraved the plates himself, stamping in the note heads and tails, at least initially; he marketed his own music, using personal charm to set up outlets, agents, and subscribers all across Europe. He even wrote his own invoices—at least some of them. (for detail, see here).

At its height, Telemann’s distribution network stretched up and down Europe—and even to America. In The Faithful Music Master, Tempesta plays a cantata that made it across the Atlantic in 1766, through Philadelphia and performed in Lancaster—the first certified spotting of Telemann in America during his lifetime, but surely not the last.

By the 1740s, when he was in his 60s, Telemann had released more than 40 printed editions, many of them large collections containing many parts. It’s a remarkable achievement for someone for whom publishing was only a sideline to his other more-than-full-time jobs.

He made money at publishing, sometimes a lot of money. But his decades-long, near-obsessive immersion in publishing suggests that there may have something other than income at stake. Perhaps it was creative freedom. He once described his inspiration as almost mystical, with “cheerful tunes” bubbling up in his head, seemingly of their own accord. “The notes always found me as soon as I looked for them.”

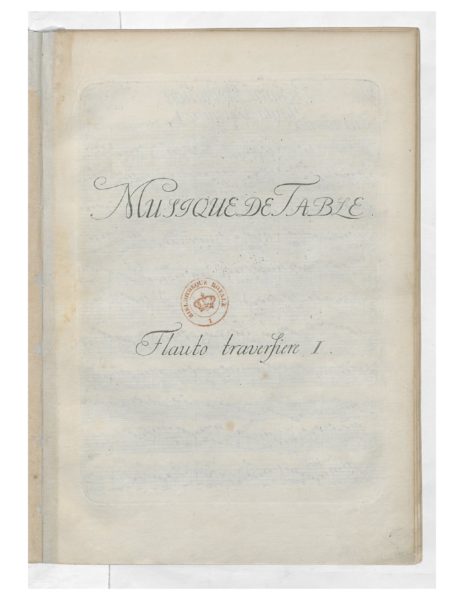

Self-publishing allowed him labors of love (to say nothing of the personal deadlines that many creative types need). The chamber music collections Musique de Table (Table Music) and the Nouveaux Quatuors (New Quartets or Paris Quartets), for instance, were his crème de la crème: gorgeous music for expert players and their discriminating audiences. They wouldn’t sell wide, but they’d sell well.

Telemann financed their upfront costs through subscriptions that he sold to people of discernment all over the continent. We can see their names in a list that he printed in the editions: German music aristocracy, Parisian salonieres, some Danish names, some Polish. And yes, J.S. Bach and G.F. Handel.

“I hope this work will make me famous someday,” Telemann wrote to a friend while he was working on the Table Music edition, almost shyly, in an aside.

Isn’t it great when a plan comes together?

____________________

Anne Schuster Hunter is a writer, writing teacher, and art historian in Philadelphia.

www.anneschusterhunter.com

NOTE: The “cheerful tunes” quote is from Telemann’s 1740 autobiography; “the notes always found me,” Telemann’s introduction to the periodical The Faithful Music Master, 1728; “I hope this work…” from a letter to J. R. Hollander, Riga, 1732/33, Letter 59 (Briefwechsel, Sämtliche erreichbare Briefe von und an Telemann, ed. Grosse and Jung, Leipzig, 1972. Translation author.

Thanks as always to Steven Zohn for his Music For a Mixed Taste, Style, Genre, and Meaning in Telemann’s Instrumental Works (Oxford, 2008), the essential handbook on Telemann.

NOTE: A manuscript copy of Telemann’s cantata, “Ei nun, mein liebster Jesu,” got to Lancaster, PA, in time to be performed at inauguration of Trinity Lutheran Church in 1766. It came in via the Port of Philadelphia, couriered in organ builder Gottlieb Mittelberger’s baggage. Read Mittelberger’s account of the journey here.

And visit Philadelphia’s Independence Seaport Museum to see the Diligence, a reconstructed full-size 18th-century schooner very like the one that carried “Ei nu, mein liebster Jesu.” Here’s a time-lapse video of the Seaport Museum’s reconstruction of Diligence, completed in 2016.