“When people play together, they start to speak a common language”

Gwyn Roberts

Covid-necessities blow up the sound

It was a sound she wasn’t expecting and it surprised her. Ulrike Shapiro, Tempesta di Mare’s Executive Director in March, talks about what it felt like in a moment during Tempesta’s much-postponed, finally triumphant orchestral tour to Berlin, Leipzig, Dresden and the International Telemann Festival in Magdeburg.

New players had joined the group on the tour because Covid and travel schedules required Tempesta to fill European musicians into a few positions. “And the European horns just brought a totally different perspective—I mean, I almost fell off my chair at the way they play the horn,” she says. “Technically it’s different. It sounds different, more robust and, you know, gritty.”

Ulrike says what was fascinating, though, was how Tempesta’s players reacted. It reveals a lot about the group. Rather than getting thrown off by this new, unexpected element in their midst, Tempesta’s players immediately, visibly, audibly, started working with it, in real time. “They took it right to new interpretive ideas of a piece,” she says

“It goes back to the idea of a corps of players, that everybody together is having this experience of something new and processing it,” she says of the entire group, strings and woodwinds as well as brass. “And you could feel them responding to it, responding to it all together, because they’re such a unit.”

There is no “I” in Tempesta

That’s teamwork for you. On this twentieth anniversary year, let’s take a moment to celebrate Tempesta as the collective miracle it is.

Gwyn Robert and Richard Stone knew from the start that teamwork would be crucial to their vision of a group devoted to lesser- and previously-unknown music of the baroque era, For the music to make its mark, it would have to be heard under the best possible circumstances: played by people who love and understand it, who are just as intrigued as Gwyn and Richard in pushing and exploring the sounds, puzzles, directions, and practices from the past that make this music come truly alive. They knew they would have to have the right team for the job.

They also knew it had to be a big team. Tempesta may have started with two people and a vision, but their goal was always an orchestra. Only an orchestra could provide the instrumental forces necessary to take on hidden gems of the 17th and 18th centuries like music for the London theater and the concert halls of Dresden, Venice, Naples, and Vienna, like music for Louis XIV’s Versailles extravaganzas. Louis called his orchestra Les vingt-quatre violons du roi or The Twenty-Four Violins of the King for a reason. In 2002 finding even close to 24 baroque string specialists would be tight—in Philadelphia especially. Philadelphia before 2002 was not an early music town.

Early music (a.k.a. period or historically-informed performance) was underway in America since at least the 1950s but Philadelphia was a late arrival. One reason might have been ambivalence here about historic performance’s gut-stringed rebels.

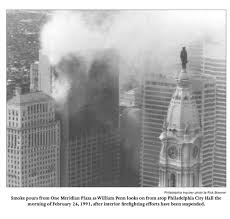

But certainly, Philadelphia was broke. Lest we forget, for decades before the millennium the city was a rustbelt basket case. New building declined, residents fled to the suburbs. In 1991, the Meridian Bank at 15th and Market Streets burned to a charred skeleton and loomed over Center City like an evil omen for 8 years. It was tough times for a lot of people, including cultural non-profits.

Still, early-music pioneers like Piffaro and Philomel launched in the ‘80’s, found their audiences and grew. A small early music community began to gain a footing. There wasn’t critical mass for an orchestra, though, despite well-intentioned attempts to start one. One of those tries had been made up almost entirely from out-of-town players. It collapsed after only one season under its own logistic weight.

An Early musician’s mecca

But then Philadelphia changed—for the better. The city, or at least Center City, began to boom. Skyscrapers and hotels shot up, the Convention Center happened. Professionals attracted by livable neighborhoods moved here in droves or moved back—including baroque music specialists. Tempesta was founded and other music groups followed suit, providing baroque players with an expanding number of gigs and colleagues.

By its tenth anniversary, Tempesta was easily able muster a full orchestra of 20 to 30 players, more than half of them local. And these musicians were well-accustomed to playing together in Tempesta’s expanding season and tours and in colleague organizations. In fact now, in 2022, many of Tempesta’s players have played in the group, or its orbit, for well more than a decade. There are even Tempesta dynasties: sisters and even a daughter have played in the group over the years.

Richard Stone likens Tempesta’s process to repertory theater, where the same artists work together again and again in different guises. For Gwyn, that familiarity of musician to musician is right there in ensemble sound. “When people play together on a regular basis in different contexts,” she says, “they start to have a common language.” It gives the group precision yoked with ease, a habit of responding simultaneously both as individuals and as a collective.

Tempesta at 20. That’s teamwork in a nutshell. And that’s inspirational.

Anne Schuster Hunter is a writer, teacher of creative writing, and art historian in Philadelphia. www.anneschusterhunter.com