The title for the orchestral program of our Telemann 360° events, Fire and Invention, quotes a letter to Telemann from an admiring contemporary composer, Johann Joachim Quantz (1697–1773), in which Quantz was explaining to Telemann why he was so fond of a certain set of unpublished pieces by Telemann that “…possess a superabundance of fire, invention and judgement….”

If I were to choose one instrumental work by Telemann that best shows his fire, invention and judgement, it might be his Violin Concerto in F, TWV 51:F4, which concludes our program. If you’re unfamiliar with Telemann’s range as a composer, this concerto, with concertmaster Emlyn Ngai as soloist, will prove an eye-opener.

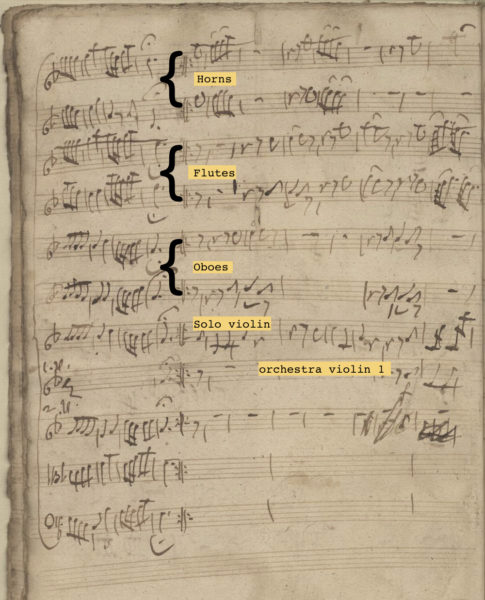

There are all kinds of surprises in it, starting with the accompanying ensemble, which is lush, to put it mildly. In contrast to the usual baroque violin concerto’s accompaniment of strings and continuo, maybe with an couple of oboes, this concerto has the soloist playing against a grand assembly of horns, tympani, flutes, oboes, bassoons, strings and continuo.

Telemann portrays the soloist as a character with a genuine interest in his orchestral comrades in this piece, with the solo violin drawing out responses of matching wit and virtuosity from the orchestra’s individual players and sections. An In an apt representation of the Enlightenment spirit, the solo violinist is more the guest at a party of peers engaged in spirited conversation than the headliner taking the spotlight.

Telemann also fashioned the opening concerto movement not in the high-baroque style of the Vivaldis and Handels of his generation, but rather in the emerging classical style popular with such up-and-comings as his godson, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach. But then, maybe by this stage in his career, Telemann is no longer strictly functioning as a baroque composer. Depending on how you define “baroque.”

This violin concerto is another concerto-en-suite, a hybrid between a concerto and a suiteof dances and character pieces. Two other character pieces in the ensuing suite, a Slavic-scented Scherzo and a hunting-horns Rondo, also cast the violin in a co-conversationalist function. The violin performs more as a traditional soloist for a “Corsicana” that always reminds me of the “Promenade” in Moussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, as well as in the trios of the concluding polonaise and a minuet.

For me, the most remarkable movement in terms of the soloist-character’s generosity of character comes about in the second part of the Allegrezza (Cheer) movement, in which the soloist, with the help of the first violin section, accompanies the wind players. It’s as though he says to the continuo group—bassoon, cello, bass, theorbo, harpischord, the iconic baroque support staff for the melody instruments and voices—take a break and let me pass around the cheese and crackers for a while.

The source for this concerto is one of the few Telemann autograph scores, which comes from the collection of the Dresden court orchestra, which in Telemann’s day his college chum, violinist Johann Georg Pisendel, led. Pisendel collected a lot of Dresden’s music by Telemann, much of it directly from the composer.

Looking over the manuscript, one thing caught my eye as particularly touching. In the upper right corner of the first page, there Telemann signed the music, “da me Telemann” (by me Telemann), surely an item meant for his friend Pisendel, a formidable violinist. Telemann knew that the Dresden orchestra had the talent on hand to play a piece where a named soloist and orchestra could stand on equal footing to great effect.

We perform Fire and Invention Saturday, October 14 at the Kimmel Center in Philadelphia.

Three contributions by Telemann to the concerto-en-suite genre survive, and we play all of them in our Telemann 360º series. You can hear the third one, a chamber concerto for recorder, two violins and continuo, in the Faithful Music Master on Friday at 8:00 at Benjamin Franklin Hall of the American Philosophical Society, 427 Chestnut Street.