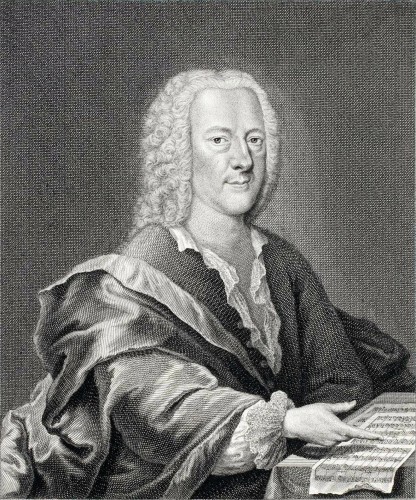

The world is throwing a grand anniversary party this year for one of the most deserving and long-overlooked artists in Baroque music, Georg Philipp Telemann.

Published in the Fall 2017 print issue of Early Music America Magazine.

Everyone seems to be celebrating Telemann’s 250th Deathiversary: festivals, broadcasts, exhibitions, tributes, and tours are taking place from British Columbia to Australia.

Ten European cities associated with Telemann during his lifetime (1681-1767), including Hamburg and Paris, formed a network last year to coordinate activities. Their calendars filled up fast. America is having a Telemann moment, too. You’ll find him on many concert programs this fall.

Philadelphia is going all out with Telemann 360°. In September and October, Tempesta di Mare/Philadelphia Baroque Orchestra and Temple University’s Boyer College of Music and Dance are doing the Sestercentennial (250th) in style. For Telemann 360°, Tempesta is organizing the biggest project of its 15-plus-year history, with two special concerts and a multi-media event that includes fameologists addressing old and new aspects of the Telemann story. It is made possible through support from The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage, The Presser Foundation, and The National Endowment for the Arts. Temple is offering a groundbreaking international conference, “Enlightenment and Postmodern Perspectives,” that will salute the old master with the kind of excitement, innovation, entertainment, and quantities of good music that would likely have delighted him.

Telemann endured some tough times before he got his party. During his lifetime, Telemann was probably the best-known and most-admired composer in Germany, if not Europe. “Lully was famous, Corelli was admired, but only Telemann is above praise,” wrote theorist and critic Johann Mattheson in the 1740s. Telemann was lionized in Paris in 1737 and offered—and turned down—impressive appointments, including the cantorship of Leipzig’s Thomaskirche that eventually went to J. S. Bach. His publications had buyers and subscribers all over Europe.

But Telemann’s reputation fell on hard times soon after his death. Most Baroque music faded in the Classical era, and most old composers were forgotten, but not Telemann. He wasn’t just not forgotten. He was scapegoated.

It was in the 19th century that Telemann got demonized. Bach was in the process of being turned into a Romantic-era type hero, a Great Man. Great Men need Little Men to pull rank on—that’s how it works. So worldly, busy, bourgeois Telemann got conscripted to serve as the facile, trivial, uninspired opposite of profound, spiritual Bach. This would undoubtedly have surprised and saddened the two men, who in life had been great friends and mutual admirers.

For the critical establishment, Telemann became the go-to “bad” composer to Bach’s “good.” Monographs, surveys, encyclopedias, and dictionaries—they all slammed Telemann. Not with validation; that wasn’t the point. Sometimes the Bach music that was praised to the heavens was in fact Telemann’s, misattributed. It’s one of those fascinating cautionary tales about the pitfalls of confirmation bias.

The “Bach is good, Telemann is bad” maxim is fading now. A more nuanced approach to the Baroque era—or any historical era—prevails. But negative appraisals of Telemann are still out there. Bad old books stay on the shelves. Edition after edition of the Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians ran a terrible article on Telemann all the way up to 1980. Today’s performers may not have read those old Grove articles, but their teachers probably did.

A wave of new fans, players, and scholars aren’t deterred, however. Interest in Telemann started picking up in the 1990s, increased in the naughts, and reached torrent proportions in the last few years. There’s a steady stream of recordings, performances, and scholarly studies coming out at this point, and it’s getting stronger.

Telemann’s big anniversary celebration marks the perfect time to meet or rediscover one of the most vibrant voices of the 18th and, increasingly, 21st centuries.

Riches to Rags, Now Riches Again

When Telemann died at the ripe old age of 84—astonishingly productive up to the end—he left a rich legacy. All his life, he’d been a whirlwind of energy, composing an enormous number of works and producing, performing, self-publishing, and promoting a breathtakingly full schedule of public performances.

He was an endearing correspondent, a charming writer, and an insatiably curious citizen of the early modern world. He heard musical possibilities in virtually everything and left a huge corpus that hits all the registers. It includes works of profound emotion that stand shoulder to shoulder with the weightiest works of his—or any—generation: the early Du aber, Daniel, gehe hin (TWV 4:17); the magisterial Brockes Passion (TWV 5:1); works of unsurpassed elegance and grace (the Nouveaux quatuors); and charming bon bons like an instrumental chorus of toads and frogs croaking counterpoint at each other (Alster Overture, TWV 55: F11).

He was on top of every trend that he encountered in his long life. And he was one of a kind, too.

To present-day players and scholars, that centuries-long eclipse in the shadow of Bach makes Telemann all the more interesting. He arrives in the 2000s virtually unexplored. It’s as if he’d been hiding in plain sight for the past two centuries. Where else can you work on an artist of such stature and be a pioneer?

“It’s great to look at a piece you haven’t seen before and realize that nobody has said anything about it before,” says Steven Zohn, a Temple University professor and author of Music for a Mixed Taste: Style, Genre and Meaning in Telemann’s Instrumental Works (Oxford, 2008), the first full-length study on Telemann in English. “When you talk about a piece by Bach, you have to spend a lot of time thinking about what other people have said. Not usually a problem with Telemann. It’s a daunting task, but also a privilege.”

Performers like the challenge of a tabula rasa, too. Playing something you’ve never heard before and possibly nobody else has heard for hundreds of years is one of those great challenges. If the work is always good and interesting, as is most of Telemann, then even more so.

Telemann’s music is particularly rich fodder for historically informed musicians because he gives them so much to work with. Telemann collected the styles that were all around him and made them his own; he could be more French than the French when he wanted to be. He listened to court music, dance music, speech, and waves on the shore and used them all. In his twenties, as part of his job, he traveled through the Polish countryside; he recalled the folk rhythms and instruments he heard there for the rest of his life. He had a genius for melody and hated being bored. He made jokes and could make you cry.

It’s all in the music, say the Tempesta players, but you have to know what you’re looking for. Musicians who speak his language find playing him to be a revelation. “In Telemann, you have to understand what the whole musical gesture is, where it’s coming from,” says Tempesta concertmaster Emlyn Ngai. “Is it French, is it German, Italian, what is he trying to do? Why is he mixing them all up? If you find the idioms, suddenly everything makes a lot of sense. And you have something that’s inspiring.”

“You don’t just play a composer like Telemann,” says Gwyn Roberts, Tempesta artistic co-director, Telemann 360° co-organizer, recorder player, and flutist.“ You participate with him. You collaborate. Telemann comes alive to a player when you come to him ready to pay attention. He builds surprises into his work—unexpected stresses, elisions, these asymmetrical phraselets. He could make a single melody line converse with itself in a way that’s uncanny.”

Roberts has played Telemann all her life: he’s responsible for the core of High Baroque recorder repertoire. She knows what treasures are in store for audiences about to discover him. “I’ve grown up with Telemann,” she says. “From day one, I’ve been aware of the incredible variety of character and nuance and melody and invention of this composer. I think as Telemann becomes better known and played with the kind of attention he deserves, he’s going to become a really distinctive voice in our culture. And he’s still going to surprise us.”

Among the surprises is the fact that Telemann was an avid gardener. “I am ravenous for Hyacinths and Tulips, greedy for Ranunculus and—especially—Anemones, and I yearn for bulbs,” he wrote to a friend. Handel was among those who enjoyed feeding Telemann’s passion. In 1750, Handel was told that one of his crates to Hamburg hadn’t been delivered because Telemann had died. When he learned four years later that his friend’s demise was a false alarm, Handel dashed off a letter: “You can imagine my joy to find you are back in perfect health.”

In 2017, we may all be feeling the same way: filled with joy that Telemann is back with us, in perfect health. He makes the world a better place.

Anne Schuster Hunter is a writer, art historian, and teacher of creative writing who lives in Philadelphia.