By Anne Schuster Hunter

When days are short and temperatures plummet, one sure-fire mood-raiser is Handel’s enduring holiday classic, Messiah. Fortunately, it’s not hard to find. It’s all around. Big orchestras with great big choirs play it, a capella groups sing it. You find it at malls, at community sing-alongs, in surprise pop-up performances, and in the back of your mind, ready to pop out with “For Unto Us a Child Is Born” whenever you chop winter vegetables or untangle the string lights for your windows.

Even though Handel actually expected it would be performed in springtime, as a message of hope and renewal in the darkest time of year, Messiah can hardly be beat.

This winter, with Handel’s Messiah, Tempesta di Mare provides an opportunity to be part of a special version: Messiah as it was first performed in Dublin in 1742. The Dublin Messiah tells a special story of renewal of its own. That first performance was of pivotal importance to Handel. It was redemptive. It changed his life.

A Reputation in Tatters

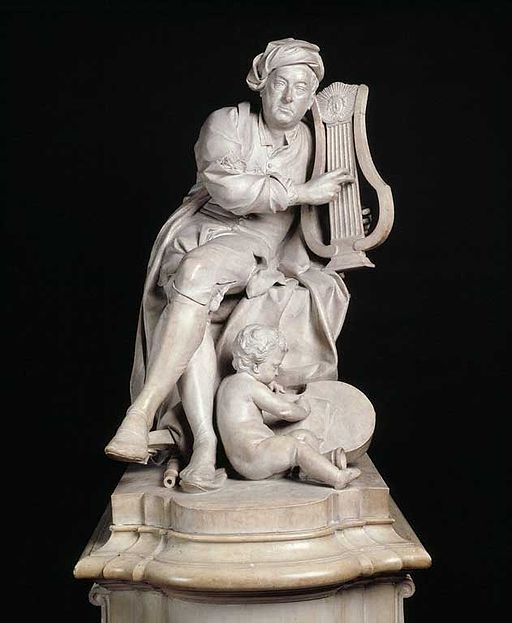

In 1740, Handel was 55 and in trouble. For decades, he’d been a wild success in London, producing a steady stream of Italian operas for a seemingly insatiable English fans. Audiences couldn’t get enough of gorgeous music, over-the-top staging and incomparable singing talent coaxed across the Channel by the tireless and powerful Mr. Handel.

Good times for Handel came to an end around 1730 when London audiences went off Italian opera. They wanted entertainment in a language they understood. They thought maybe Handel had become too big for his britches. And the antics of Handel’s high-strung divas and divos started to seem annoying. Handel tried to rekindle the flame but over the course of a decade, as series after series of opera flopped, audiences stayed away and London opinion turned hard against him. One contemporary account claims that people even tore down flyers posted for his shows.

His finances failed and so did his health. He suffered from intermittent paralysis in his right hand. His reputation was in such tatters that in far-away Berlin, King Frederick the Great wrote to a friend that he’d heard “Handel’s great days are over, his inspiration is exhausted and his taste behind the fashion.” Handel talked about giving up and quitting. But he didn’t. He went to Dublin.

It might have begun as a retreat, but it turned out to be a recharge. He stayed for almost two years, building a repertory company from the ground up—so different from the massive forces and budgets he’d been responsible for in London—and to all appearances enjoying it immensely. You can practically feel him unwinding as he tells a friend about his first concert there. “Without Vanity the Performance was received with a general Approbation,” he wrote. Everything was wonderful. The soloists—only one of whom he’d brought from London—“please extraordinary,” or are “very good,” the chorus members “do exceeding well,” the instrumentalists are “really excellent,” and “the Musick sounds delightfully in this charming Room.”

Words Conspire to Transport and Charm the Ravished Heart and Ear

He refocussed. His stubborn resistance to English-language productions—oratorio—started to melt. The success of Messiah in Dublin on April 13, 1742 must have helped, with rhapsodic reviews like:

Words are wanting to express the exquisite Delight it afforded to the admiring crouded Audience. The Sublime, the Grand, and the Tender, adapted to the most elevate, majestic and moving Words, conspired to transport and charm the ravished Heart and Ear.

In fact, Handel never wrote another opera after Dublin. He returned to London in 1742 and jumped back into big-time theater, offering a full season in 1743—but only oratorios, all in English. No Italian. No opera. Samson, the first performance of his return, was a resounding success and after that, it was all blue skies and a new, fabulously successful oratorio career. He and London fell back into a love affair that lasted until his death in 1759.

Messiah, of course, went on to become classical music’s sweetheart. Later versions got big, literally. Handel scored the Dublin version for instruments that could reasonably be found in a secondary center: strings, with the addition of trumpets and drums. But later, for London, he added bassoons, oboes and horns. After his death, Messiah grew even bigger: 800 performers were advertised for a 1787 performance, 2,500 in 1857, and so on. Right now, the Mormon Tabernacle Choir has a “World Largest Virtual #Hallelujah Chorus” online, with “300+ members of the choir combined with 2,000 voices worldwide.”

You can imagine Handel the Showman up in the afterlife purring happily at the sheer, audacious size of it all. But Handel the Artist? The Dublin version, after all, is the one that turned his life around.

______________________________

Anne Schuster Hunter is a writer and art historian living in Philadelphia. She offers a creative writing workshop at Temple University Center City. www.anneschusterhunter.com.

NOTES: About flyers, anonymous letter in London Daily Post, April 4, 1741, quoted in H. C. Robbins Landon, Handel and His World (Little, Brown, 1984), quoting from O. E. Deutsch, Handel: A Documentary Biography (London, 1955); Frederick the Great, October 19, 1737, quoted Robbins Landon quoting Deutsch; letter from Handel to Charles Jennens, December 29, 1741, quoted Robbins Landon quoting Deutsch; review in Faulkner’s ‘Dublin Journal,’ May 11, 1742, quoted Robbins Landon.