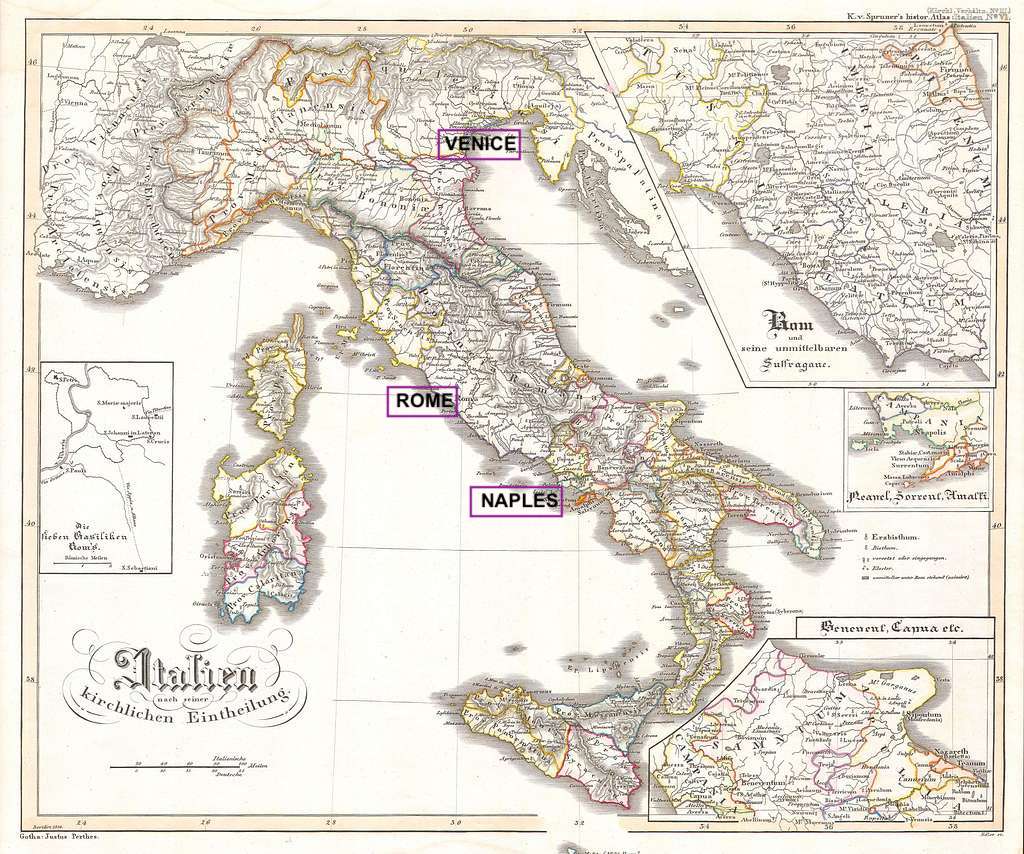

What makes baroque music from Naples sound recognizably different from music from Venice and Rome, the other main centers of Italian baroque style? Much mention is made on forums like these—program books, liner notes and concert write-ups, not to mention in countless scholarly texts—about Neapolitan style in baroque music. But it’s rare for anybody to tease out what about it makes it sound different. I myself hear the music from Naples as distinct from the other two but, in honesty, I have never tried to put my finger on what about it is different.

Let’s see if we can get down to some brass tacks on this topic. To achieve this, it helps to describe traits in styles that are more familiar from which we might then contrast Neapolitan traits. Bear in mind, there has always been cross-fertilization going on in the arts, so any sort of stylistic purity is out of the question.

A quick note before diving in. If any of the following discussion below doesn’t ring a bell, just listen to a few recordings of each composer mentioned and everything will fall into place.

What’s going on in Venice?

The most famous hallmark of early baroque Venetian style is a call-and-response, polychoral style associated with the composers of San Marco Basilica such as Giovanni Gabrieli (1557–1612) and Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643), a late-renaissance attribute that continued into the early baroque. Monteverdi’s two surviving middle-baroque operas, Il ritorno d’Ulisse (1639) and L’incoronazione di Poppea (1643) are great illustrations of Venetian vocal and instrumental approaches at the time. They are filled with “madrigalisms”, musical gestures meant to imitate patterns of speech or evoke specific moods.

By the eighteenth century, Venice was most strongly identified with Antonio Vivaldi’s (1678–1741) rationalized, formal stamp on the concerto and aria as a vehicle for instrumental as well as vocal exuberance. His structural approach was so widely adopted internationally as to become a commonplace, making it easy to forget that it originated in the Most Serene Republic.

And what about Rome?

Baroque music from Rome, originating from the ecclesiastical center point, is overlaid with a sense of judicious restraint more in keeping with sacred pageantry, in contrast to Venice’s sense of outright spectacle. Roman music really came into its own during the middle baroque, ca. 1640, best exemplified in the secular vocal music of Luigi Rossi (1597–1653), Giacomo Carissimi (1605–1704) and Antonio Cesti (1623–1669). Their melodies display easy-flowing lines with an aesthetic derived from sacred choral writing, but setting worldly texts and amplifying human emotion. Their triple-meter (think waltz, minuet, barcarolle) writing in particular relished in mutations of beat placement that are only possible within triple time.

This restraint passed forward into high-baroque Rome through the formally disciplined sonatas and concertos of Arcangelo Corelli (1653–1713) and a purely instrumental idiom that exploited what was violinistic rather than vocal. This resulted in an attractive angularity of melody that fits fine on a fiddle but is not particularly singable.

That brings us, finally, to Naples

To appreciate what was distinctive about Naples, it’s necessary first to go back to the 1500’s when, in order to project Neapolitan intellectual prowess, the young nobility shifted their ambitions from excelling at military pursuits to the intellectual and creative arts. Naples was already unparalleled as a center of musical education, and these young nobles took full advantage of it for themselves. One who achieved fame in music was Prince Carlo Gesualdo (1566–1613), whose distinctive, mannerist madrigals made an indelible impression on composers everywhere, opening up expressive possibilities previously unimagined. Gesualdo’s approach remained so popular that compositional innovations from Venice would not yet break into Neapolitan composers’ vocabulary until the 1630s.

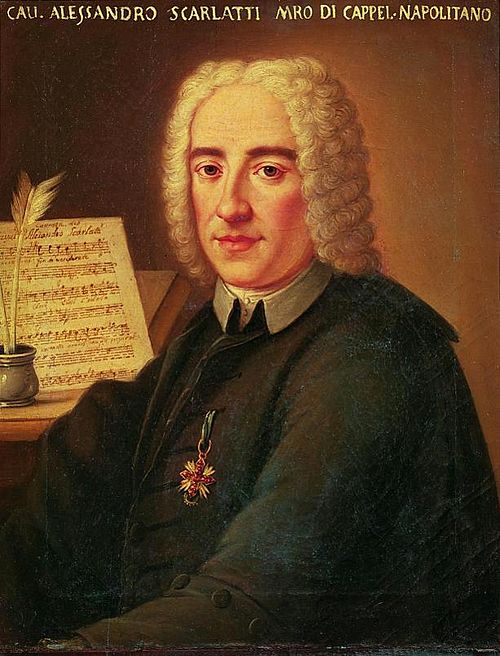

Two of the composers that played a major role in the development of the aria during the “high baroque”, from ca. 1690 onwards: Alessandro Scarlatti (b. Sicily 1660–1725) and his lifelong deputy, Francesco Mancini (1672–1737). They contributed a couple of very important formal innovations: the da capo aria, without which Handel operas wouldn’t be Handel operas, and a virtuosity with fugal counterpoint that would make a North German blush. In addition to this, they gave their compatriot Gesualdo’s mannerist tendencies an eighteenth-century freshening-up. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Scarlatti’s chamber cantata “Bella s’io t’amo il sai” / “Ardo, è ver” with its surprising and often shocking harmonic and vocal turns.*

The Neapolitans’ music conservatory system was the ace up their sleeve that made their composers sought throughout the continent. By the time you’d finished at a Neapolitan conservatory you would have such a solid grounding in structured improvisation and counterpoint that you could compose an entire opera as fast as you could commit it to paper, with the composer’s imagination being the only limit. If you were a Mancini or a Scarlatti, you were as quick on the draw at mentally working out a complete layout for setting a musical idea as an orator would be with a topic for argument.

* Available on recording from multiple artists, including Tempesta di Mare with Philadelphia soprano Clara Rottsolk: Scarlatti Cantatas and Chamber Music, Chandos 2009.