Three Pieces for lute that share the stage in comfort.

As I practice my way through the opening show of Tempesta’s very different 2020–2021 season, a program that happens to be my solo lute recital, I sometimes feel like I’m listening to the lute-music equivalent of a Three Tenors concert, with each piece a true star that enjoys both equal billing and comfort on stage with the other two. My “three tenors” are Weiss’s Sonata in A minor, WeissSW 43, Muffat’s Passacaglia grave, and Bach’s Pièces pour le luth à Monsieur Schouster, BWV 995.

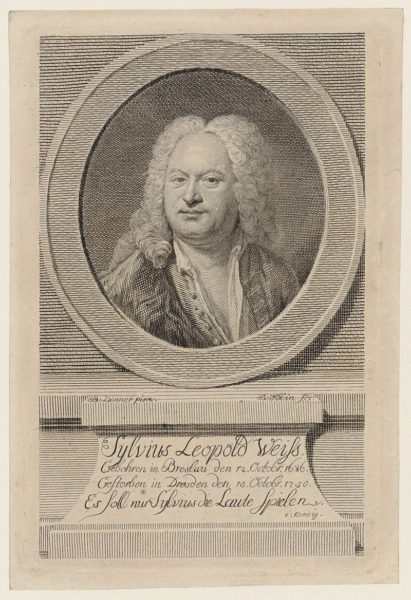

Weiss: Sonata in A minor, WeissSW 43

Silvius Leopold Weiss (1687–1750) was the greatest lutenist-composer of the eighteenth century both by contemporary accounts and present-day reckoning. He worked at the court of Dresden as a member of its storied Hofkapelle, a roster that consisted of singers, instrumentalists and performer-composers deployed in orchestra, chamber music, church and opera.

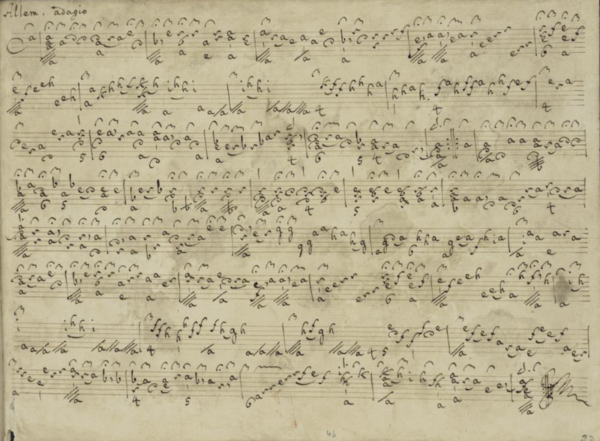

The WeissSW catalogue lists 109 pieces, most of them multi-movement suites that he called sonatas. This sonata in A minor is an undated work from a manuscript in the Dresden Hofkapelle archive, a collection that’s still housed in that city. It shares enough common compositional features with dated late works, ca. 1740–1750, that I am confident that this one is also a late piece. Some of Weiss’s late-work features include sequences made up of asymmetrical units of threes rather than symmetrical units of twos, and smoke-and-mirrors enharmonic modulations that leave you with a “wait…what just happened?” sensation.

A distinctive feature that you will hear through this sonata is Weiss’s use of a persistent, recurring melodic fragment—called a motif—a noteworthy device to employ at the time. Though the motif is a mere pickup-plus-downbeat figure at the unison (same note), it lends the sonata a greater feeling of unity and rationality. I read Weiss’s employment of the motif device as his signaling an embrace of the Enlightenment—the Age of Reason—to the listener. The movements with this figure are the allemande, courante, sarabande and presto, not coincidentally the four core movements of a classic baroque solo suite.

Of this program’s three works, only this one began life as a lute piece.

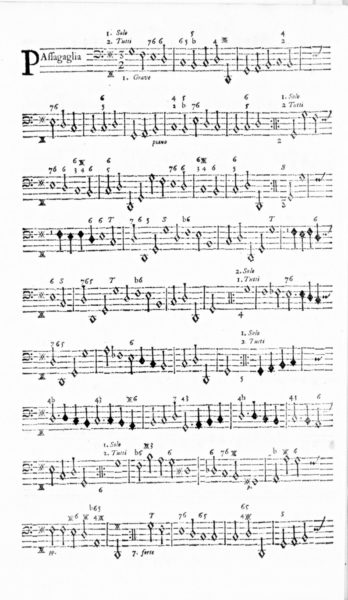

Muffat: Passacaglia grave

Georg Muffat (1653–1704) was among the vanguard of composers who introduced and promoted French musical style as defined by Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632–1687) in German-speaking lands. Muffat also left one of the most valuable legacies for the baroque music revival by having documented French music’s coded notations for “authentic” readings of its rhythms, which he’d observed in Paris. This French-style Passacaglia grave first appears in his 1682 publication of sonatas for string ensemble, Armonico Tributo. He revised and reissued the same piece as “Ciaccona un poco grave” to end his 1701 collection of twelve concerti grossi, Auserlesene Instrumentalmusik.

“But what does a piece for string orchestra have to do with a lute concert?” I hear you ask. Recently I learned that an Austrian lute composer, monk at the Benedictine abbey at Kremsmünster and contemporary of Muffat, Pater Ferdinand Fischer (1652-1725), transcribed the Passacaglia grave for lute. Since this piece is one of my top favorites, I pounced on the opportunity to include Fischer’s lute version on this program. Fischer omitted some of the less lute-friendly passages from his version, which I took the liberty of reuniting with his existing transcription for this performance.

My friend, Viennese lutenist and Fischer-evangelist Hubert Hoffmann, has spent considerable time at Kremsmünster researching Fischer’s life, music and even his playing technique as evidenced by Fischer’s instrument, which remains at the abbey to this day. The notes of Hubert’s CD of Fischer’s original compositions quotes from his obituary, mentioning how by playing, he knew how to make the solitude of his cell sweeter (cellae solitudinem dulciter temperare novit). I found this particularly touching.

Bach: Pièces pour le luth à Monsieur Schouster, BWV 995

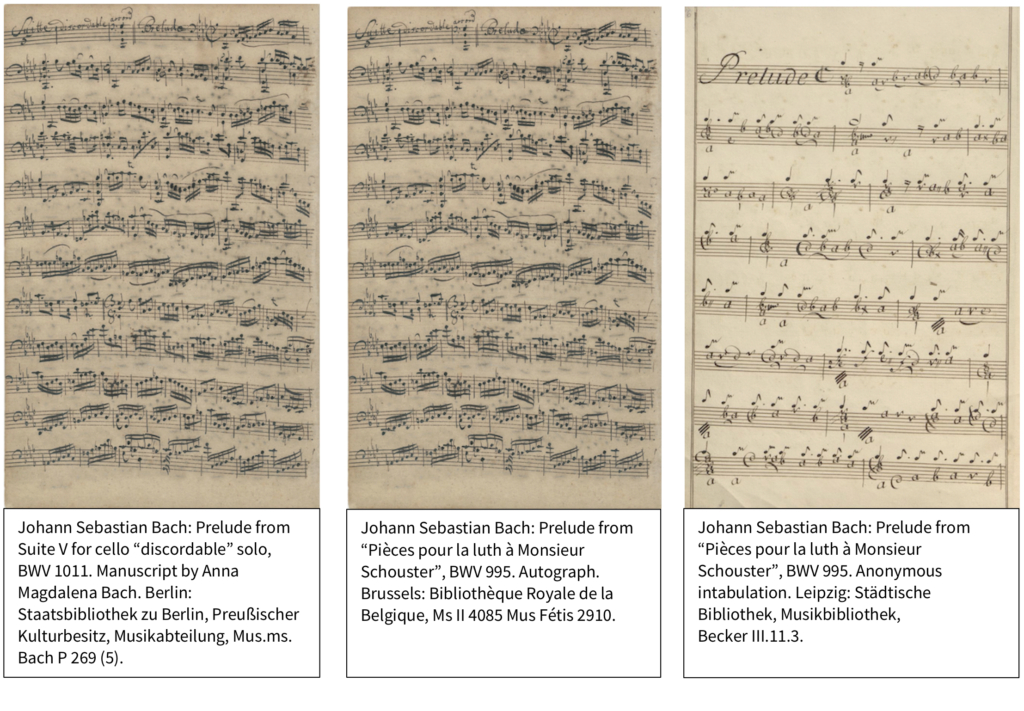

The Pièces pour le luth à Monsieur Schouster also did not begin life as a lute piece but took a different route from the Muffat to becoming one.

Though there’s no evidence that he himself played lute, Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) liked the instrument enough to have included it in major vocal works including the St John and St Matthew Passions; to have written at least two original solo lute compositions and adapted other preexisting pieces. He also transcribed one of Weiss’s lute solos for keyboard and, by adding a fanciful descant for violin, transformed it into a duet (WeissSW 47 and BWV 1025).

The Pièces pour le luth of ca. 1730 falls into the adaptation category, his revision of the 5th suite for unaccompanied cello, BWV 1011, from a decade earlier. This suite not only offers a fascinating glimpse into the compositional process with its added counterpoint and harmonies, but also suggests a meta-story that highlights how Bach may have viewed the lute within solo suites as a larger aesthetic concept.

Though the suite is a French form, only the fifth of the six cello suites is most thoroughly French in style. But more than that, Bach cast it in a notably archaic French style rather than the popular “German mixed style” version of French. It’s a style that Bach knew from his study of Jean-Henri d’Anglebert’s keyboard music, a style that in turn borrowed liberally from the French lute school of d’Anglebert’s time. Admittedly this is purely a personal take on it, but it is my impression that Bach, in choosing to recompose the fifth cello suite as a lute solo, had taken the germ of his original musical ideas full circle, reassigning a suite to the lute—complete with its anachronistic French title—whose stylistic legacy is the lute music of the previous century.

Richard Stone is a lutenist, and Tempesta di Mare’s co-founder and co-artistic Director.