It wasn’t just an item on the bucket list, Telemann’s visit to Paris. It was a victory lap.

In 1737, Georg Philipp Telemann, who at age 56 had never left Germany—or extremely near environs— anytime in his life, finally went traveling. He r.s.v.p.’d “yes” to a group of French musicians who’d been inviting him and made the big trek from his home base in Hamburg, up between the North and Baltic Seas, to Paris. Eight months later, after a triumph-filled sojourn, he headed home “full of pleasure from it and in hopes of returning,” as he wrote later.

He never went back. Old theater impresario that he was, perhaps he knew not to mess with a really big finish. Sequels are almost never as good.

Tempesta di Mare’s Chamber Players salute Telemann’s big Paris adventure and the music that brought it about with Paris Quartets. They’ll play three chamber works that predate the famous trip, from his Quadri (Quartets) of 1730, and two of the Nouveaux Quatuors (New Quartets) from 1738, during it. Together, they give us a feel for the moment, one we all dream of, when we receive approval from the people we admire the most. Would that we all had a Paris Quartets in our lives.

No, other than the magic eight months in Paris, Telemann never left Germany. Except for the jaunt to Paris, he may never have traveled farther south than Frankfurt. He lived out his life in a circle of German cities around Dresden until he moved north to Hamburg at age 40 and stayed there until his death almost 50 years later.

The Whiff of France

The man himself was a stay-at-home. But his music roamed the world. From his northern perch, Telemann absorbed all the currents of music flowing through Europe—and anticipated some others—sampling them, inhabiting them, making a distinctly modern sound with them. Music like this was called “mixed taste” and Telemann was an undisputed master.

The two main influences in “mixed taste” were Italian and French style. Arguing over which one was better, by the way, was one of the great amusements of cultured people of the time—like long, interminable conversations in recent eras over the Yankees vs. the Boston Red Sox, or Marvel vs. DC comics or Cardi B vs. Nicki Minaj, or Bach vs. everybody else.

Telemann was supremely comfortable in both French and Italian styles. In his Italian mode, he could absolutely dash off thrilling, runaway sequences and meltingly sweet arias. But the elegant, social-dance-inflected French style permeated his senses. As he put it in one of his autobiographies, it was “in his ears,” so that even his Italian-style concertos “whiffed of France.” He preferred French music for its melodies, he said, and its “easy cheerfulness.”

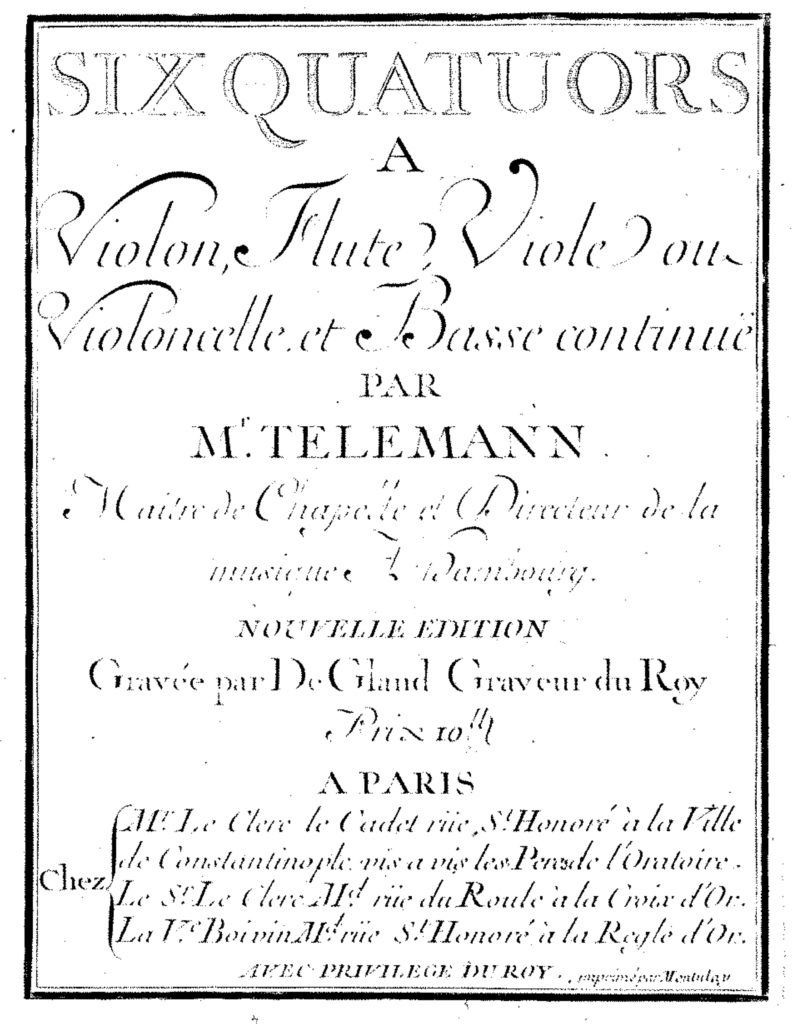

It must have been particularly sweet to this dyed-in-the-wool German Francophile when in midlife, he found he’d picked up a lot of French fans. By the 1730s, the number of French subscribers to Telemann’s printed editions was second only to the number of Germans. Not only that, but in that era of lax copyright control, the French paid him perhaps the ultimate compliment: pirating him. Among the unauthorized editions was a lavish, deluxe bootleg of the Quadri issued by Charles Nicholas Le Clerc’s publishing concern. In a forward, Le Clerc gushed that:

Telemann’s quartets are so universally praised that the public will be overjoyed by this new edition, more beautifully engraved and printed on paper than any previously issued…

Telemann always had Paris

The French did him proud, he found. Among the extraordinary performances he experienced in Paris were performances of his own work. In his 1748 autobiography, he described an 18th-century supergroup—perhaps with Telemann on harpsichord—playing the Nouveaux Quatuors in concert:

The admirable way that Herrn Blavet, traversoist, Guignon, violinist, Forcroy-the-son, on viola da gamba, and Edouard, violoncellist, played the quartets deserves to be described, but words do not suffice. It’s enough to say that they attracted the rapt attention of court and city and brought me kudos from all sides, along with mountains of good will.

And then, the eight months were over. Telemann went home and his busy life back up. There were Parisian ripple effects, of course. His reputation in Germany, big before, was now enormous thanks to the Paris trip, though. He continued to be a celebrity in Paris, too, where he remained an item in newspapers and his music stayed in play for decades.

And there were the memories. Telemann always had Paris. A few years later, in 1751, he was exchanging letters with friend and colleague Johann Gottlieb Graun. They were debating—what else?—Italian vs. French. Graun thought French opera recitatives seemed awkward compared to Italian, that they changed tempo at random.

Oh, Telemann replied, tempo changes like that don’t cause problems for French people.

And to explain why not, he referred to a delectable luxury item that had only recently become au courant among Parisian trendsetters and, apparently, their honored guests. French recitatives, he said, just flow on and on, “like champagne.”

Bubbling on like champagne. Victory is sweet.

______________________________

Anne Schuster Hunter is a writer and art historian in Philadelphia who leads a creative writing workshop at Temple University Center City. www.anneschusterhunter.com

Quotes:

Telemann, Autobiographie von 1740, in Johann Mattheson, Grundlage einer Ehren-Pforte, Hamburg, 1740. Reprinted Rampe, p. 382:

…und schied mit vollem Vergnügen von dannen, in Hoffnung des Wiedersehens.

Telemann, “Brief An Herrn Mattheson,” Frankfurt, 1718. Reprinted in Siegbert Rampe, George Philipp Telemann und seine Zeit, Laaber-Verlag, Laaber, 2017, p. 362:

Zum wenigsten ist dieses wahr dass sie mehrentheils nach Franckreich riechen. Ob es nun gleich wahrscheinlich dass mir die Natur hierinne etwas versage wollen weil wir doch nicht alle alles können so dürffte dennoch das eine Uhrsache mit seyn dass ich in denen meisten Concerten so mir zu Gesichte kamen zwar viele Schwürigkeiten und krummer Sprünge aber wenig Harmonie und noch schlechtere Melodie antraff wovon ich die ersten hassete weil sie meiner Hand und Bogen unbequehm waren und wegen Ermangelung derer letztern Eigenschafften also worzu mein Ohr durch die Frantzösischen Musiquen gewöhnet war sie nicht lieben konnte konnte nach imitiren Mochte.

Telemann, in a text for a 1721 “Winter Concert,” quoted in Eckart Klessmann, Georg Philipp Telemann, Ellert & Richter Verlag GmbH, Hamburg, 2004, p. 46:

Was Welschland schmeichelndes in seine Sätze schliesset:

Die ungezwung’ne Munterkeit

So aus der Franzen Liedern fliesset;…

Le Clerc, quoted Klessmann, page 76:

Die Quartette Telemanns sind so allgemein gelobt, dass man glaubt, der Öffentlichkeit mit einer neuen Ausgabe, die schöner gestochen und auf besserem Papier gedruckt is als alle bisher ershienenen, eine Freude zu bereiten. Es bleibt zu hoffen, dass die hierauf verwendete Sorgfalt nicht nur der Schönheit dieses Werkes entspricht, sondern dass sie auch von grossem Nutzen is für eine vollendete Aufführung.

Telemann, Autobiographie von 1740, Rampe, p. 382:

Die Bewunderungswürdige Art, mit welcher die Quatuors von den Herren Blauet [sic], Traversisten; Guignon, Violinisten; Forcroy dem Sohn, Gambisten; und Edouard, Violoncellisten, gespielet wurden, verdiente, wenn Worte zulänglich wären, hier eine Beschreibung. Gnug, sie machten die Ohren des Hofes und der Stadt ungewöhnlich aufmercksam, and erwarben mir, in kurtzer Zeit, eine fast allgemeine Ehre, welche mit gehäuffter Höflichkeit begleitet war.

Georg Philipp Telemann, Briefwechsel, sämtliche erreichbare Briefe von und an Telemann, ed. Hans Grosse and Hans Rudolf Jung, VEB Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig, 1972, p. 282.

Die Tactveränderungen machen dem Franzosen gar keine Schwierigkeit. Es lauft alles nach einander fort, wie Champagnerwein.

As always, many thanks to Steven Zohn of Temple University for his magisterial Music For a Mixed Taste: Style, Genre and Meaning in Telemann’s Intrumental Works, Oxford University Press, 2008, the singular resource on Telemann.