“This work, I hope, will make me famous,” G. P. Telemann wrote, in a candid moment, to a friend about music he’d just finished and was sending to the publisher, his Musique de Table (Table Music) of 1733.

Reaching for the stars

At age 52 in 1733, Telemann was already an international name and had been writing weighty projects like Passions and opera for decades. You wouldn’t think he’d peg a collection of chamber work—pieces for one, two, three, or a handful of instruments and considered light entertainment —as his bid for the heights of musical Olympus.

But he did. And he was right.

In The Four Winds, Tempesta di Mare performs a quartet from Musique de Table, now famous, along with a selection of other chamber works by Telemann’s contemporaries. The show’s got a special twist, though. It’s all for woodwinds; there’s nary a string in sight (except for lute and cello on the bassline).

Color, focus and edge

Under leadership of Co-Artistic Director Gwyn Roberts, a flutist and recorder player, Tempesta has always featured winds. But an all-wind show is new. Tempesta oboist/recorder player Priscilla Herreid approves. “Much of what winds do in orchestras is color and provide focus and edge to the string sound. And that’s not a bad thing,” says Herreid. “But this is a totally different concept. This is really about what we do as soloists in our own right, as chamber musicians in our own right.”

And they get to shine. Among special moments in the program are a movement in the Telemann where the bassoon plays an unexpected, rip-roaring bass solo over two sweet, treble flutes. And a Jacques Loeillet sonata pairs baroque flutes with voice flutes (lower-pitched members of the recorder family)—a combination so rare that this might be its only example. The instruments’ voices, so similar and yet so different, play off each other like an aural new taste sensation.

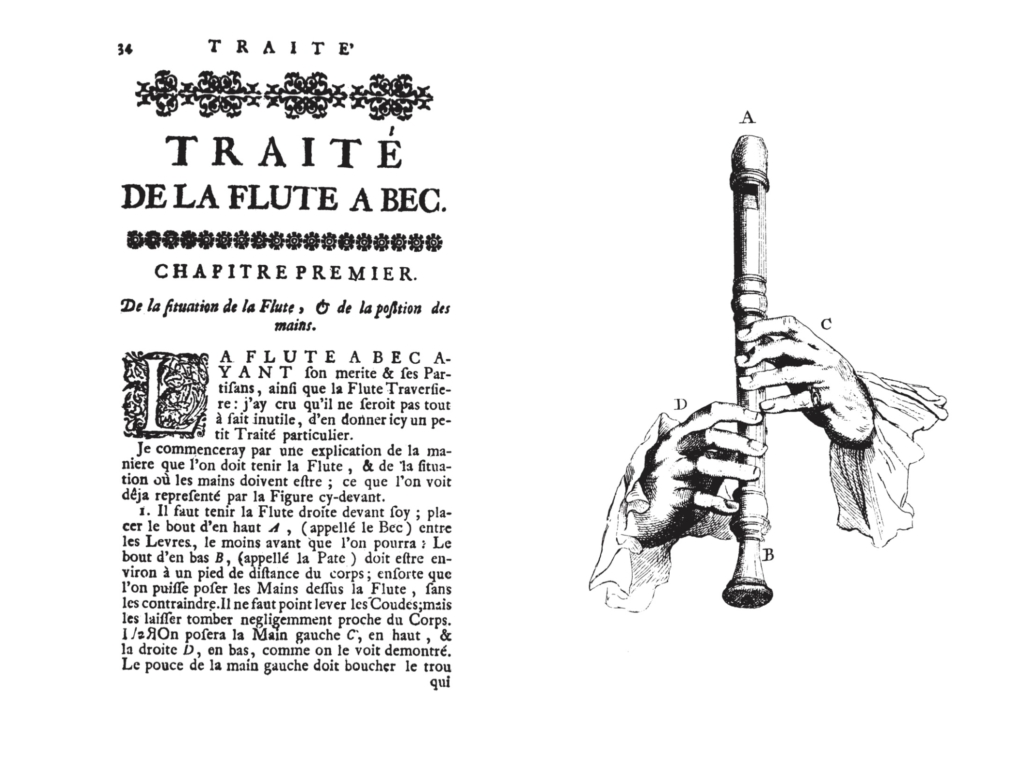

The Baroque produced a large quantity of small-group wind music like The Four Winds’ (a treasure-trove for present-day players). Wind instruments like recorders, flutes and double-reeds were wildly popular in the period and publishers and composers rushed to make sheet music available for professionals and for avid amateurs—not, perhaps, as much as string music, but a substantial amount.

Theorists wrote treatises on woodwind playing; instruction manuals, tunebooks and arrangements of everything from Italian opera to folk tunes proliferated. There were wind superstars, like flutist Michel Blavet in Paris, and wind superfans, like Frederick the Great, King of Prussia, an amateur flutist so avid that he installed his flute teacher, J. J. Quantz, at court in Berlin, to have him at his side.

Adolph von Menzel, Frederick the Great Playing the Flute at Sanssouci, 1852

Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin; Wikipedia.

People played in capitals like London and Paris and also in colonies and far frontiers. Chamber music was performed on concert stages, in elegant salons, in banquet halls and in modest living rooms, too. J. F. Schickhardt’s concerto for four (count’em, four) alto recorders—the finale of Tempesta’s Four Winds program—must have delighted parties of music-playing friends in home get-togethers as much then as it does now.

The Four Winds was postponed in spring 2020 due to Covid-19 and now, with restrictions continuing, can allow only a few people to attend the live performance. In the Covid-time, our salons may be where our screens are, but this music accommodates handsomely. Put some snacks on a tray, pour a glass of something nice, settle back and prepare to be entertained! Pass the salsa?

Anne Schuster Hunter is a writer, teacher, and art historian in Philadelphia. She conducts a creative writing workshop at Temple University Center City. Find out more: anneschusterhunter.com