RESTORATION, 2008

Performing Editions from War-Damaged Manuscripts

excerpted from 2008 program notes

Last season, when we premiered four pieces by Fasch on this series, we mentioned that it was difficult to describe the feeling of discovering music that’s not just new and outstanding, but which is also full of out-of-the-blue surprises that exceed one’s most optimistic expectations. That is what it was been like to transcribe these Fasch manuscripts, to hear them for the first time in centuries, and to spot a unique voice among High Baroque composers, whose quality of work is right up there with Bach, Telemann and Handel.

This summer, we also had the good fortune of going to Dresden to examine the manuscripts first hand. Maybe it’s corny, but touching the same paper that Fasch and his concertmaster Pisendel wrote on gave the process of bringing all these new-to-modern-ears pieces to this series an extra frisson.

When we first started looking at the manuscripts from Dresden three seasons back, we recognized one reason why Fasch is less well known today than he could be. The major source of some of his most adventurous compositions, the holdings of the Dresden library, was badly damaged during the Second World War. Despite the best efforts by archivists to protect the collection by moving it to an underground vault, percussions from the bombings caused the foundations to crack, allowing groundwater to seep in and flood the vault. Many historic items—including music by Fasch—were damaged or destroyed by mold or ink corrosion.

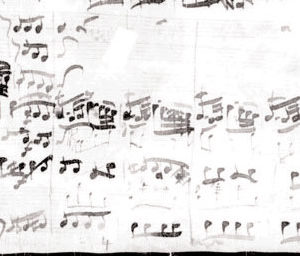

Here is an illustration of some of the damage. This image comes from a high-resolution photo. You’ll notice that there are notes galore, but the staff lines can become impossible to discern.

The ink of those lines got washed away in the flooding. Since they were drawn by hand with a five-tip pen (called rastrum), they are not necessarily straight, so you can’t just figure out where the lines should begin and end and then overlay new staves to see where the notes lie. Luckily, though, there is almost enough information in the digitized picture to be able to enhance the lines with graphics software.

In fact, the illustration above shows a bit of the music that opens tonight’s program, the single movement Concerto in F. There are two versions, both in the Dresden library. One is this water-damaged original in Fasch’s own hand, which is fragmentary and runs out of music about halfway through, the remainder presumably lost or destroyed. The other is an incomplete set of partbooks in a copyist’s hand which contains the full length of the movement. Both versions are similar enough to have made it possible for us to reconstruct the complete piece.

In his day, Fasch was especially famous for his orchestral suites, a sequence consisting largely of French dances—e.g., bourées, minuets, gigues, etc.—that typically begins with an overture movement. Bach’s four orchestral suites and Handel’s Water Music, are just two famous examples of this popular form, though the Handel suites lack the ouverture. Grove Music Online, the world’s leading music encyclopedia, lists 87 orchestral suites by Fasch.

The manuscript partbooks from which we transcribed this [Suite in F] have identical material for both the oboes and flutes for great stretches of the work, including in the solos. When it comes to the wind solos, one would imagine they would be either for the flutes or for the oboes, but not for both at the same time. This is a problem which the Dresden concertmaster Johann Georg Pisendel, who championed Fasch’s music at Dresden, solved for us. Pisendel noted in his own partbook when the solos should go to flutes, and when to oboes. We are happy to follow the judgment of the concertmaster who led this suite’s eighteenth-century premiere, and we perform the woodwind solos as he specified.

Richard Stone & Gwyn Roberts