Ric3. What Makes the Weiss Lute Duets Special

What’s particularly fun about playing these duets with my duo partner is how music for two lutes pretty much doubles the compositional possibilities of what’s achievable in solo music. The duet format allows for all kinds of fancy melodic and contrapuntal maneuvers at high speed in the treble, while letting the bass move faster and more expressively. None of this is readily achievable on one lute alone. And since baroque lute technique is mainly two-voiced—treble and bass—two lutes opens the door for rich, four-voice textures, i.e., two independent trebles and two independent basses. It’s like suddenly discovering a musical superpower.

But the four Weiss lute duets also display two big formal departures from Weiss’ solo lute music that his fans may find surprising: sonata da chiesa (church sonata) form and a majority of through-composed movements.

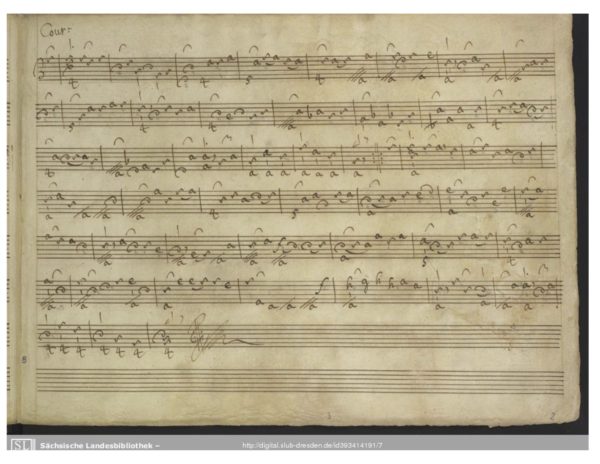

The most familiar Weiss solo form is the French-derived dance suite with a core, six-movement sequence of allemande, courante, bourée, sarabande, minuet and gigue as its basic scheme. By contrast, Weiss’ scheme for his duets is a four-movement, Italian-derived sonata da chiesa form. The scheme of a sonata da chiesa is to alternate its movements slow-fast-slow-fast. The sonata movements are named by abstract, Italian tempo indications (i.e., allegro, largo), not by concrete, French dance forms (i.e., courante, sarabande). The absence of dance in the sonatas is what gives them their da chiesa qualifier.

Binary form is the norm for Weiss’ individual suite movements, and also the practice of his German, high-baroque contemporaries. A binary-form movement is divided in two with notation showing the performer where the first half of the movement can repeat before moving on to the second half, which can also repeat. But the duets reverse this distribution with the majority of their movements being through-composed. A through-composed movement is notated to go from beginning to end without repeats.

In terms of the solo suites’ and duets’ relative scales, a six-movement suite with its repeats hovers around 25 minutes, while a 4-movement duet runs around 14 minutes. Repeats are not mandatory, so performance time can be—and often is—shortened by omitting repeats.

While even the user-friendliest Weiss solo suites come with a certain level of challenge for the performer, these duets are on par with his most practice-intensive solos, with a range of difficulty from challenging to extreme. The fact that Weiss demands the performers’ technical-all in these duets promises a level of compositional élan beyond anything in his already-impressive solos.

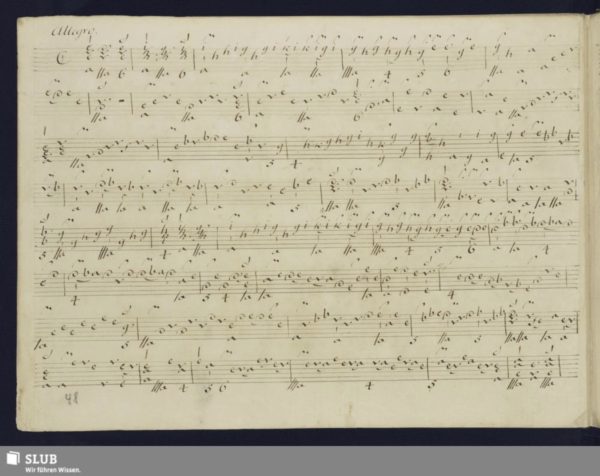

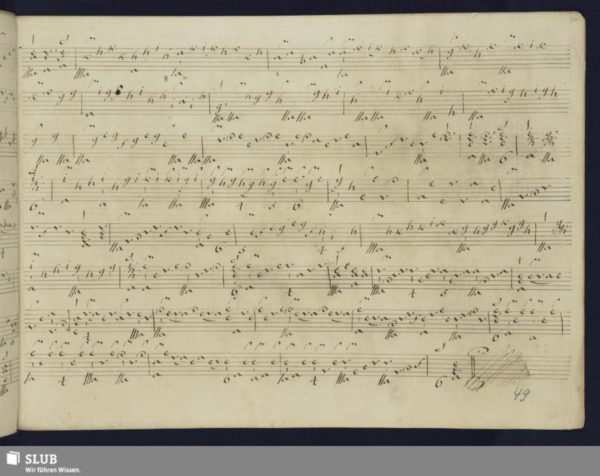

The duets on our recital all come from the so-called “Dresden” manuscript that forms part of the royal collection at the Dresdencourt where Weiss worked most of his career. You can view this music online at the website of the Säschsische Landes- und Staatsbibliothek in Dresden, where the royal collection is preserved. All of it is in lute tablature, the preferred notation for the lute from the instrument’s heyday in the Renaissance to its demise in the classical/Enlightenment period. Tablature represents where the left hand is placed and when the right hand plucks, so each tablature only works with a specific intended instrument, be it lute, theorbo, or guitar.