4. Weiss’ Ensemble Music, Reconstruction, and the Duets Themselves

Only seventeen Weiss ensemble works remain today, though inventories list 70 concertos, trios and duets. For fifteen of these, only single lute parts remain, such as the solo part for a concerto, or one of the lutes for a duet. Luckily the lute plays throughout the pieces, so the harmonic structure and melodic elements for all the music remain largely intact. Of the remaining works, two survive intact: a recently rediscovered lute duet and a trio with flute and cello.

The extant parts themselves reveal such excellent music, you can only wonder what the music would have sounded like with all their missing parts restored. If you want to play these pieces, you have to reconstruct the lost parts. That is what I finished over the summer for these four duets on our Artist Recital Series, as well as for four concertos and two other duets with flute that went to Prague in 2000 and became Tempesta’s first recording on Chandos.

A lot of people have asked how you reconstruct incomplete music…

The answer is: it’s not that different from supplying missing anatomy to a damaged statue. If you know your anatomy and if you know the style specific to the sculpture, you can fill in the blanks to make a believable, albeit speculative, stand-in for the original. The musical analogy to art restoration is knowing your musical form and formal procedures (musical “anatomy”) and the style of that composer and his circle.

If anybody wants to talk about reconstruction in greater detail, just ask! It’s a favorite topic.

Meanwhile, here’s a little about the duets in the order they were played. Cameron took the surviving parts, and I took the reconstructions, along with a solo interlude for each of us.

All four of these sonata da chiesa duets follow a similar progression of mood and intensity. The first movements are playful but gentle; the second movements energetic and heady; the third movements slow, in a minor key, and with a high degree of pathos; and the fourth movements lighthearted and forthright.

Sonata in A major, SC 60, for two lutes

1. Vivace — 2. Allegro — 3. Largo — 4. Presto

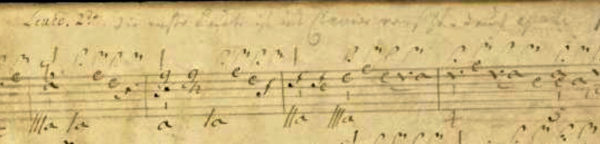

The surviving part for this duet is marked “lute 1”, and this is the only one of the four Dresden duets that doesn’t mention an alternate orchestration. The pace with which the surviving part switches back and forth between primary and subsidiary-sounding material suggests that the two lutes are equals. The second movement identifies itself as being in concerto form through use of the “three-stroke” trope associated with so many high baroque concertos. Here, Cameron plays three chords in the first measure—short-short-long—under which I play faster notes in harmony with those chords. These chords and their rapid harmonization constitute a three-stroke, whether used together or separately. It functions thematically, signaling syntactical openings throughout the movement, similar to the way initial capitals mark the start of a new sentence.

Sonata in D major, SC 59, for two lutes

1. Spiritoso — 2. Allegro assai — 3. Un poco andante — 4. Allegro

The surviving part for this duet is lute 2 and bears the annotation in German: *“Lute 1 is arranged for harpsichord and is elsewhere.” As with the duet in A, the writing for the surviving part suggests two equal lutes. The duets in A and D might have been produced around the same time, because some of the musical tropes that Weiss employs in the first two movements lend a “family resemblance”. The first movements of both use a jaunting, long-short rhythm throughout as a unifying device. While the Spiritoso of this duet is tuneful, the Vivace of the A duet is more angular. The Allegro assai of the D major duet uses fast scale passages as primary, thematic material, whereas their occurrence in the other duet functions to link larger structural sections.

Sonata in C major, SC 54, for two lutes

1. Andante — 2. Allegro I & II — 3. Largo — 4. Tempo di minuetto

Lute 1 is the surviving part for this duet, which has the annotation, “Lute 2 is also arranged for the harpsichord.” The second movement in particular posed something of a puzzle for its reconstruction: should the missing part be melodic against lute 1’s arpeggios, or should it join with lute 1 by playing the same patterns in harmony? The entire first section of this binary movement has nothing but arpeggios, mostly in a single rhythm, without anything distinctly melodic. But after two bars of silence at the beginning of the second section, lute 1 changes very briefly to a shape that works well against the same kind of arpeggiation it plays at the beginning. I chose that shape as the basis from which to derive melody for the missing lute. The lutes switch roles in the second allegro, in C minor, in which lute 1 has the melodic passagework, and therefore lute 2 needed to do something to support that. The finale particularly lent itself to an approach with passages in four voices: two independent melodies, two independent basses.

Sonata in B flat, SC 56, for two lutes

1. Adagio — 2. Allegro — 3. Grave — 4. Allegro

The duet in B flat’s surviving part is lute 1, to which someone added the comment “the second lute elsewhere and [arranged] for harpsichord.” This duet comes with a surprise: the lute 1 part of Dresden has a twin in a British Library manuscript. The difference is that the London version belongs to a “Concert d’un luth et d’une flûte traversière.” Maddeningly, its flute part is missing.

It isn’t possible to know which version came first: lute-lute, lute-harpsichord or lute-flute. One factor is certain: Weiss toured with his Dresden colleague, the flautist Pierre Buffardin, and he would not have made a flute part out of a lute part that would lie awkwardly on flute. The reconstruction of the missing lute part needs to be easily adaptable to sound good on flute. I had earlier reconstructed a flute part with this in mind for Tempesta di Mare’s tour to the Prague Spring Festival in 2000, which later went onto the same Chandos recording as the four Weiss lute concertos. I later engineered an idiomatic lute part from the flute part.