It was May 2018, early summer in the town of Kroměříž…

Kroměříž is about 250 miles east of Prague and so postcard pretty that it’s been called the most beautiful historical city in the Czech Republic. It’s not Venice or Florence or one of the other cultural hubs that have stirred imaginations for centuries. But it has beautifully-preserved baroque architecture and the Archbishop’s Palace, a spectacular castle with such authentic and meticulously-maintained grounds that UNESCO made them a World Heritage Site. The palace also has an important music archive, and during that week in May, Tempesta di Mare’s Richard Stone was there to take a good hard look at its holdings in 17th-century music.

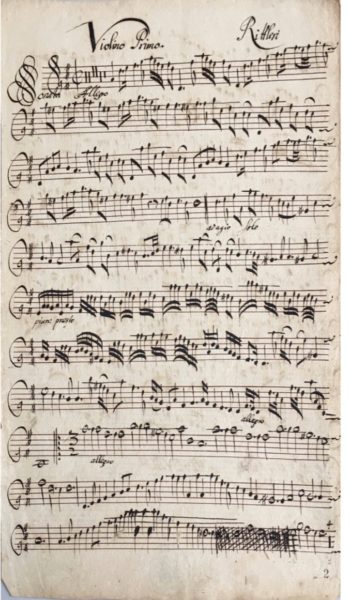

For days, he pored over precious, fragile manuscripts, furiously tapping into his laptop and making photographs for reference back in Philadelphia. The weather was balmy, the warm sun brought flowers out in the gardens. But for Stone, in the Palace’s library, it was Hanukkah, Epiphany, Winter Solstice, St. Lucia Day, St. Nick’s Day and Christmas all rolled into one.

Tempesta di Mare’s Czech Christmas program is drawn from the exciting discoveries he made there, all of them unpublished, most previously unknown, some of them by well-known composers and some with no name attached at all. “And they’re stunning,” he says.

Stunning—and eye-opening, too. The Czech show is a Christmas show, with seasonal treats like Jacomo Carissimi’s nativity cantata. But it has a bigger message, too. This is a show that gives modern listeners a new angle on one of the most exciting, beautiful, and relatively unexplored areas of European art music.

The early baroque period of the 1640’s to ‘80’s, the generations after Monteverdi but before Vivaldi and Bach, is one of those eras in cultural history when things were changing, everything was in flux. A new impulse toward expression and emotionalism (shorthand: “opera”) started in Italy and spread rapidly through Europe. Places like Kroměříž might be off the beaten path, but its artists caught the spirit.

Those mid-17th-century styles made a strong impact. The archive shows the high quality and progressive nature of international music that was played in Kroměříž. It also shows, in works like the Sonata Natalis by trumpet virtuoso Pavel Josef Vejvanovsky, Moravian musicians’ warm reactions and response.

Kroměříž offered fertile ground for change. It had real motivation for putting the past behind it and embracing something new. Around 1650, the town was at low ebb. Kroměříž had been pummeled during the Thirty Years War (1618-1648), surviving two brutal occupations by the Swedish army in 1643 and 1645 and a devastating bout with the Black Death (bubonic plague) soon following.

But then it got its lucky break and a second chance. The Habsburg Prince-Bishop of nearby Olomouc, formerly of Salzburg, made a pet project out of reviving Kroměříž. Over the course of decades, he poured a fortune into the old medieval town and turned it into a baroque showcase. A connoisseur with apparently impeccable taste, the Bishop bought well, hired well, and commissioned well, leaving the town with the magnificent Palace, a significant art collection, and superb music—including the manuscripts that so impressed Richard Stone.

There’s so much more out there in the world than the hot spots we’ve all heard of. As interest grows in mid-17th-century music, enthusiasts like Stone are making their way to places like Kroměříž with laptops and smartphones and avid audiences back home to bring these sparkling, hopeful sounds back to life. It’s rebirth and renewal, in just the right season.

Happy solstice, all.

Richard Stone’s research was made possible with a grant from The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage.

Anne Schuster Hunter is a writer and art historian in Philadelphia. www.anneschusterhunter.com