1721. The title of Tempesta di Mare’s program might have you scratching your head. You might be wondering whether you forgot something special about 1721. It’s not usually a marquee date, after all. It’s not 1619 or 1776 or 1929 or 1939—or 1984 or 2001.

In the absence of troubles

And that’s the beauty of 1721. Nothing much happened in 1721. There was a blissful absence of bother, upset, calamity in 1721 (something to which 300 years later we aspire with all our hearts). In the absence of troubles, wonderful things—like amazing music—could finally grow, and so they did. Tempesta’s 1721 offers some of the cream of the musical crop.

The European world was confronted with something new in 1721: peace, prosperity and good fortune. It had been a long time coming. 1721 followed more than a century of disasters. From the beginning of the Thirty Years War in 1618 to the end of the War of the Spanish Succession in 1714, war had been unceasing. As had disease and famine. Over and over, plague erupted. It took so many lives—a million in France in 1628-31, in Italy in 1629-31, in Naples in 1658—that the so-called Great Plague of London in 1665-’66 (100,000) was puny in comparison. Early death touched so many families. Both of Bach’s parents died by the time he was 10, as did four-year-old Telemann’s father; both composers lost young wives.

Boom follows bust

But at the turn of the century, in the first years of the 1700s, it was as if storm clouds parted. War was over; plagues took a break; agriculture bounced back; town and country rebuilt, cities grew. The death toll dropped, the economy boomed and merchants, townspeople, and shopkeepers flourished (investors and speculators did too, as did the slave trade, but those are different stories). People could finally take a deep breath and regroup. They stopped waiting for the next blow to fall. They relaxed.

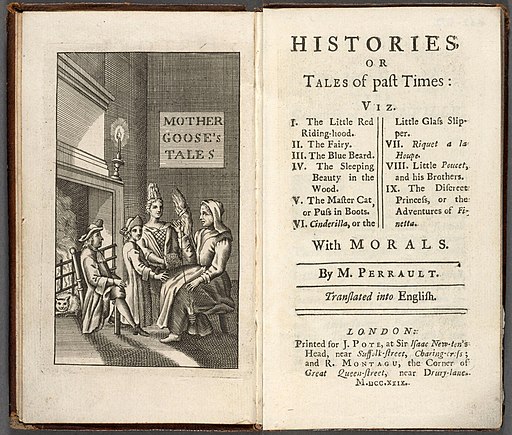

And they started enjoying themselves, in greater numbers than ever before. They shopped. They strolled in newly rebuilt, lush gardens, they sipped champagne and coffee, they went sight-seeing—royals, nobles, and commoners, too, who were experiencing greater prosperity as commercial tides rose. People recreated. People read, and not just religious and philosophical tracts but frivolous literature too, like The Thousand and One Nights (1704), science fiction like Cyrano de Bergerac’s The Other World: Comical History of the States and Empires of the Moon (1657, illustrated edition 1708), romances, travelogues, Don Quixote translated into German, French and English, even fairy tales like Mother Goose by Charles Perrault (first edition 1697).

Music exploded

And they adored music. They played it, they heard it, they dressed up and went to concert halls to look at each other and listen to it. Music exploded, with 1721 becoming a musical annus mirabilis. Some of the music we now love best came from this period.

Take J. S. Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos (Brandenburg #4 is on Tempesta’s program). The Brandenburgs came about during Bach’s six-year employment with Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Köthen in northern Germany. The prince celebrated the era’s new prosperity—as many other landholders did—by launching an extreme makeover to turn the ancestral home into a fashionable baroque palace. The project included hiring a first-class orchestra and a first-class leader for it, Bach. With a decent budget, expert players and an appreciative patron, Bach spent his thirties flourishing. This is where he wrote not just the Brandenburgs, but also the solo cello suites, the violin partitas, and the Well-Tempered Clavier.

Telemann’s creative frenzy

Bach’s friend Telemann, aged 40 in 1721, took a different route. Having decided against a courtier’s life in favor of the free republics during a boom economy, he’d turned the busy commercial center of Frankfurt into a music hub. With almost superhuman energy, he founded ensembles and public concerts, made music for affairs and events, started a publishing operation and generally developed an open, vibrant music culture that channeled and nurtured that ebullient 1721 spirit—at the end of the year moving his activities to Hamburg and even bigger arts audiences.

The selections by Locatelli and Dall’Abaco in 1721 are typical of the kind of brilliant repertoire Telemann-as-producer would feature in his concert programs. His own contribution to 1721 is the suite Les nations anciennes et modernes. Les nations… shows how Telemann was the perfect composer for the time. It’s colorful and poignant, deep and quirky, the perfect thing to enjoy at a show and discuss afterwards over coffee and wine with friends.

300 years later, in 2021, may this joy soon be ours.

Anne Schuster Hunter is a writer, teacher of creative writing, and art historian in Philadelphia. www.anneschusterhunter.com

Note: not to disregard the marquee appearance of the date 1721 in Stephen Coss’s The Fever of 1721: The Epidemic That Revolutionized Medicine and American Politics, 2016, about politics, medicine and journalism around a smallpox outbreak in 18th-century Boston. Terrific!