Westminster Bridge, with the Lord Mayor’s Procession on the Thames; WikiCommons.

A sweet story circulated about Water Music during George Frideric Handel’s lifetime. It’s sweet, but unfortunately it’s also not true—the dates don’t work out. It’s worth taking a moment to give it a look, though, because it may have been Handel himself who told the tall tale (it appeared in Handel’s first biography and so may have been among Handel’s late-life reminiscences with his biographer). If it’s what the old master liked to tell himself about the origins of one of the best loved, long-lived pieces of music in the western canon, well, that’s interesting.

First, the facts:

On a lovely, temperate, London evening in July 1717, lady and gentleman merrymakers boarded barges on the Thames at 8:00 pm and set off to enjoy a leisurely three-hour cruise up the river to a dinner party. They got to Chelsea at 11 pm and at 3 am, after eating, headed back downriver, disembarking at 4:30 am.

King George I himself, in his Royal Barge, led the party. A City Barge followed, big enough to hold a full baroque orchestra—basses, bassoons, oboes and flutes, strings and brass, fifty musicians in all—which serenaded the revelers with Water Music, composed especially for the occasion by London’s bright star, Handel. The orchestra played all night, playing up the river and back and during dinner, too. Onlookers, eager to be part of the scene, rushed to their own boats; before long the river filled with a happy throng.

“He caus’d it to be plaid three times”

The stunt got great reviews. The Daily Courant provided a glowingly detailed description with the special note that the king was so pleased with the music that “he caus’d it to be plaid over three times in going and returning.”

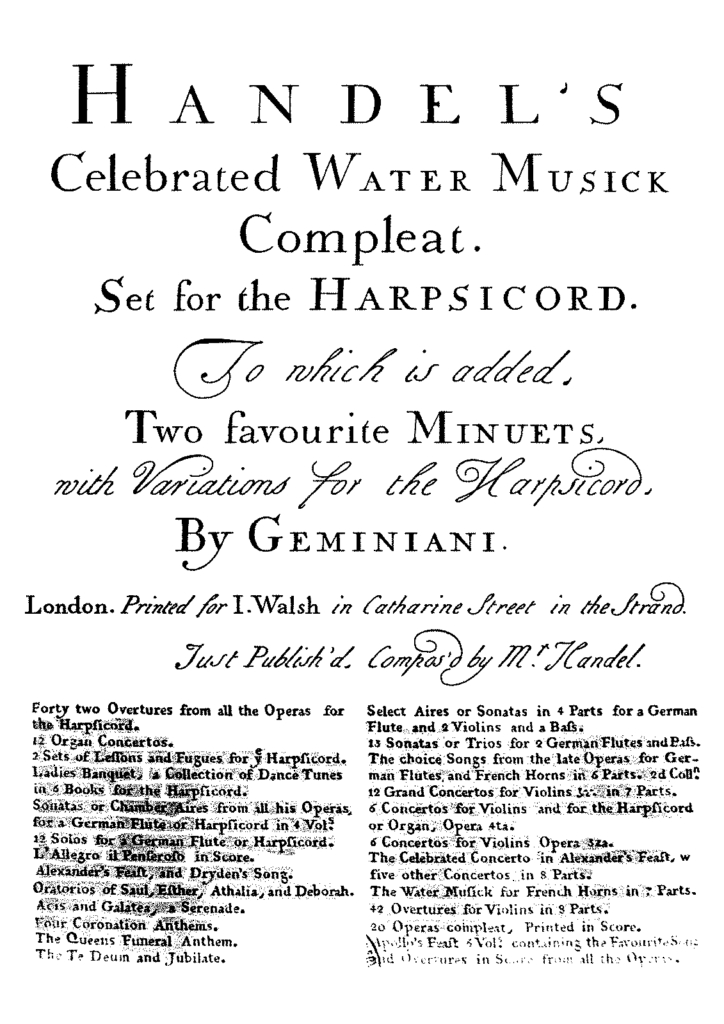

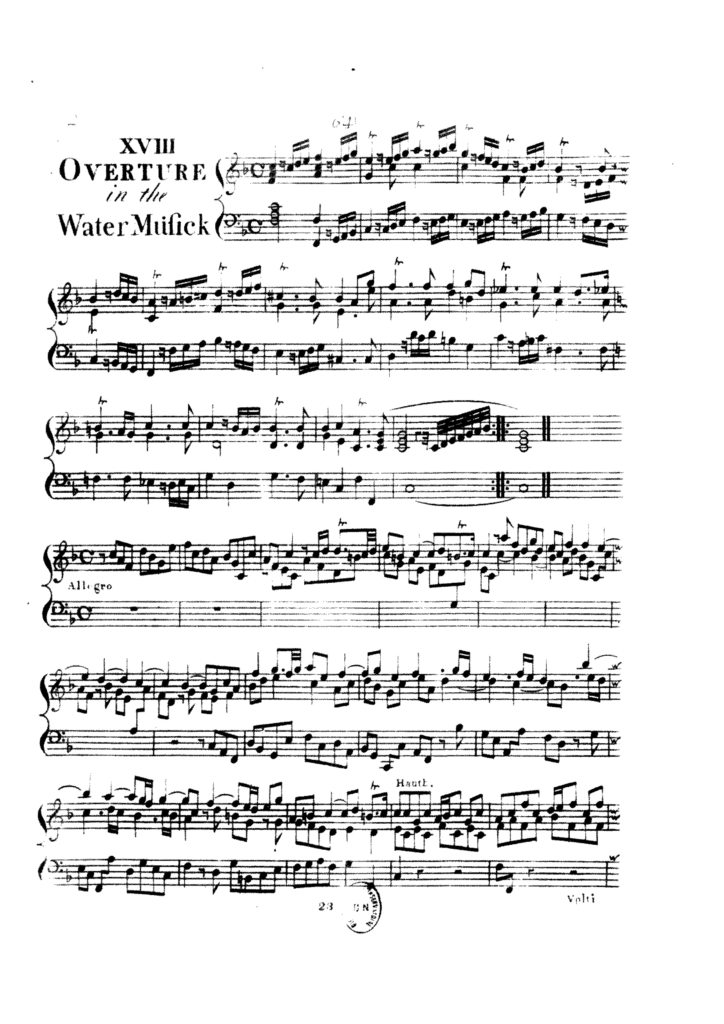

The barges were hardly moored when Water Music exploded on the cultural scene. Publishers and fellow-composers set to providing arrangements of Water Music for small groups, big groups, solos for home performance, for pub bands, for tea orchestras. Water Music was everywhere and would be for a very long time.

These Two go way back

It was a night to remember.

And remember it Handel did. The story—the one that he himself may have told his biographer—gave the incident the kind of character conflict and resolution that would have been natural to an old opera-hand like Handel. It said that the King and Handel were at odds in 1717. Nearly ten years before, they were together in Germany, where the future King George I of England was Saxony’s very German Elector of Hanover and the equally German Georg Friedrich Händel was his Kapellmeister. The beef between them, if such there was, is that Handel took a temporary leave from his post in Hanover to visit London in 1710 and essentially never came back. Elector George was supposed to have been offended.

Georg Friedrich Händel (ca. 1726-1728). WikiCommons

King George I, ca. 1714. WikiCommons.

When Elector George became King George I and joined his increasingly-English Kapellmeister in London (Handel actually became a citizen in 1727), the success of Water Music was supposed to have effected a reconciliation between the two of them. And then they rode off together into the sunset. Sweet. Except the story’s bunko, because the two reconciled long before 1717.

It may speak to a certain emotional, if not factual, truth, though. It shows the extent that Water Music was a source of warm feelings for his boss. If not reconciliation, what else might have been going on?

A Public Relations Stunt?

It’s possible that George was particularly grateful to Handel for the music that gave him a big relations win at the right time. George was having a rocky reign. He was massively unpopular. Many of his subjects loathed him from the moment of his ascension to the throne, if not before, considering him—not without reason—to be a foreign interloper foisted on their beloved country by the Whigs.

No fewer than 20 anti-George riots erupted on his Coronation Day alone and they were not the last—a Jacobite Rebellion had been suppressed as recently as February 1716. It didn’t help George’s case that he never gave up the position of Elector of Hanover, that his personal affect was cold and aloof, and that he [apparently] either wouldn’t or couldn’t ever speak English.

The torchlit cruise, however, gave him a chance to be seen publicly enjoying himself in the quintessential English activity of “messing about in boats” (the Water Rat’s description in The Wind in the Willows: different century, same river). And Water Music would provide a long, warm reminder of the happy moment for many years to come. If Handel eventually chose to remember his boss’s happiness with him and his own pleasure in the event in rosy, relational terms, well, who are we to quibble?

300 years later, that sense of well-being still radiates from Water Music. Perhaps hidden in the music is an invitation to go back to that night and join in. Let the golden sound of paired horns dance in your mind like ripples on the river’s surface, the music says. Close your eyes, launch your mental barge, sit back, breathe deep, and slip away.

At least once, if not “three times, going and returning.”

Anne Schuster Hunter is a writer and art historian in Philadelphia. www.anneschusterhunter.com.