(Wikimedia Commons)

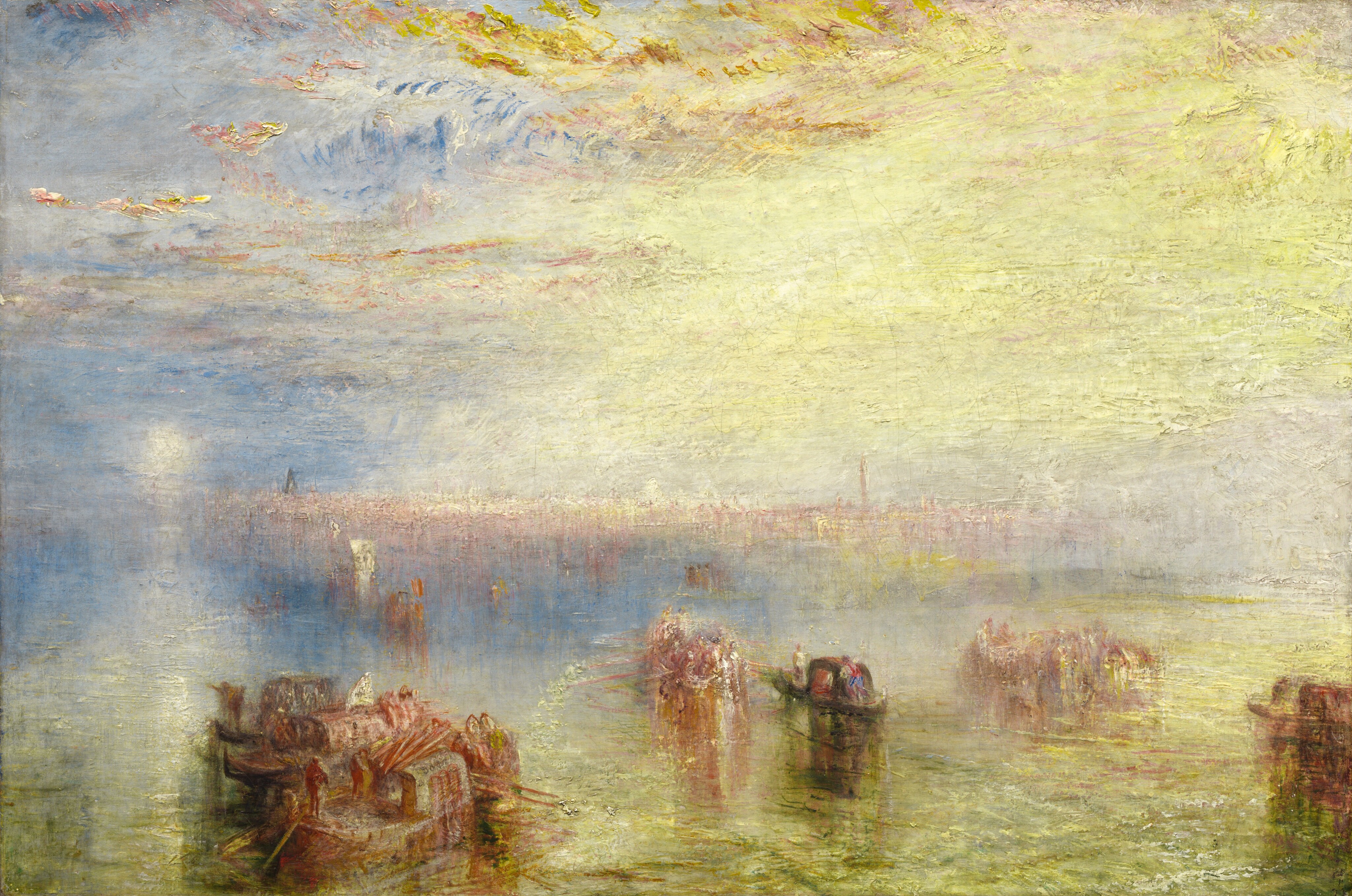

Ah, Venice. The Rialto, the Grand Canal, the Cathedral of San Marco, the piazzas, mists, stones, beaches, veils of golden light, “La Serenissima.” The city holds a special place in the imagination. In Death in Venice, Thomas Mann’s protagonist called it “the incomparable, the fabulously different place.”Venice is sui generis. Venice is special.

So it makes sense that one of the most different, or even downright weird, episodes in the history of baroque music took place in Venice: that during the 17th and 18th-centuries, Venice mustered a force of exceptional singers and orchestral musicians from, of all places, its orphanages. And they were all female.

Professional Female Music-Stars

It wasn’t a gag. The musicians of Venice’s Ospedale were, many of them, stellar artists who made a vital contribution to their city’s culture for many, many years. In an era and place in which few woman—no matter their class or privileges—were allowed to hold jobs or even walk down the street alone, women who would have been society’s discards were able not just to carve out decent lives, but to amass proud professional accomplishments. In their upcoming program, Tempesta di Mare presents The Women Behind the Screen to honor the exceptional achievements of the women musicians of Venice’s Ospedali.

The Ospidali orchestras came about to some extent by serendipity. Venice, never a monarchy, since medieval times a Republic, was run through government and non-government organizations. Ospedali—literally, “hospitals”— were founded as entities under boards of governors as early as the 14th century to care for the city’s orphaned and abandoned children.

Photo Tony Hisgett (Wikimedia Commons)

For centuries, the Ospedali sheltered their charges and prepared them to live meaningful, God-fearing lives. For boys, that meant training for trades. The trades weren’t open to girls, so girls were taught domestic skills. In renaissance Venice, though, those included music. Eventually, domestic training morphed into a demanding music program.

Which met its historic moment in the 1600s. The republic of Venice was losing its world domination in manufacturing and trade but growing in entertainment and tourism, given that it was already one of most popular travel destinations ever. The world’s first public opera house opened in Venice in 1637 and more followed. Opera and music of all kinds was the rage, and not just during Carnival.

Hungry Public Demand

With a corps of trained musicians, a virtually limitless talent base (however involuntary), and hungry public demand, the governors of the Ospedali found themselves sitting on a goldmine and took advantage of it. Four of the Ospedali put together ensembles, cori, of their best playersand instituted regular concerts, open to the public, under general admission.

Gabriele Bella (Wikimedia commons)

The concerts were popular, very popular, not just with a curious public and tourists but with cognoscenti who declared them superior to commercial fare. They brought in a healthy income for the institutions—particularly during Lent, when the Ospedale could put on shows but Venice’s churches couldn’t—and they encouraged deep-pocketed donors.

Educating and training the young musicians was done by the cori’s own seniors—many of whom also became in-demand teachers for children of the wealthy. But with new revenue, the governors brought in outside professionals too, male maestri, to augment staff and train the wards in the most up-to-date, fashionable, crowd-pleasing styles.

Antonio Vivaldi was one of these maestri, as well as other international luminaries such as Niccolò Popora, who’d trained world-famous castratis Farinelli and Cafferelli, and Johann Adolph Hasse, husband of legendary mezzo-soprano Faustina Bordoni—what a role model for the Ospedali’s fledgling opera singers!

Well, not opera. The governors would never have allowed the orphans to offer such potentially provocative repertoire under their watch (they were fine with oratorio, though). Always aware of their duties to protect the morals of their charges and to keep their institutions’ reputations squeaky-clean, the boards kept their wards on a very tight leash.

Keeping them behind the curtain

When the cori performed in public, they did so only in their own concert halls where they were concealed behind curtains on specially-designed grated balconies above the audiences.

Moreover, there was no mingling with outsiders. Even visiting outside or taking a day’s holiday was rare and required special permission from the Ospedale administrators. Potentially, wards could leave to marry or enter suitably upper-class households. But many didn’t and remained institutionalized for life as boarders and charges of the Ospedali.

Which does beg quality-of-life issues. But consider the alternatives. There were few good outcomes for female children born or thrown into destitution in the 18th century and many very bad ones. Even women with class privileges had extremely limited personal freedom at the time. The opportunity to develop a profession, pride, status and sometimes even personal savings—well, at least some of the wards of the Ospedali may have felt truly blessed. And to the exceptionally musically gifted, Venice gave a highly improbable, even unique, chance to live their best life.

Rapturous first-person accounts describe the 18th-century Ospedale concerts. They say that music floated above the audience as if wafting from the clouds.

Was it heaven? No, it was Venice.

There is growing interest and active new research into the musicians of the Ospedali, as thoroughly documented in the truly fascinating recent dissertation by Vanessa Tonelli, “Le Figlie di Coro: Women’s Musical Education and Performance at the Venetian Ospedali Maggiori, 1660-1740.” PhD Dissertation. Northwestern University, 2022.

Anne Schuster Hunter is a writer and art historian in Philadelphia. www.anneschusterhunter.com.