Don’t worry—the instruments in Broken Consort are in perfectly good shape. Nobody dropped a flute. The violin is fit as a fiddle. “Broken consorts” are just called that because in the Queen’s English, Elizabethan style, “broken” sometimes meant “mixed.” A “broken consort” is a “mixed consort,” that is, a group of different kinds of instrument playing together, like violin with flute, lute, and viola da gamba. It’s another example of the English using ugly words for a very nice thing, like “Eton mess” or “spotted dick” (delicious desserts), “snogging” (canoodling) and “Benedict Cumberbatch” (Benedict Cumberbatch).

And “Broken Consort” is very nice indeed. Tempesta di Mare’s upcoming program of English consort music includes some of the most engaging and beautiful music in the baroque period—or any period, really. Using small musical forces—only three, four, five or six instruments, sometimes with voice, sometimes without—composers in early 17th-century England created music that reached levels of emotiveness and creativity that have rarely been equaled.

Lovely tunes and exquisite sensitivity

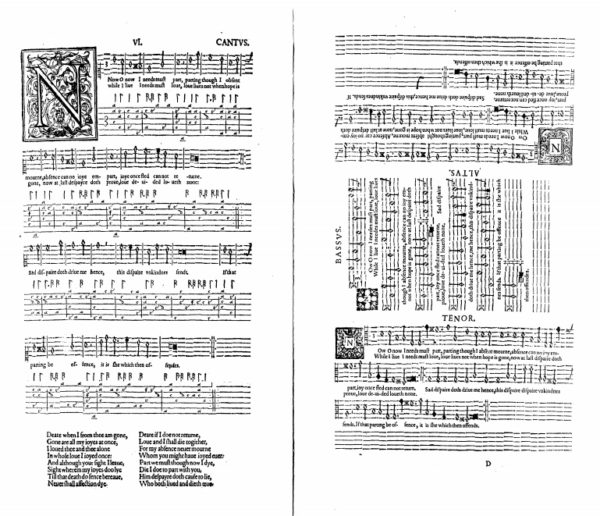

The songs of John Dowland are a great case in point. For voice with multiple instruments or for voice with lute alone, Dowland’s songs combine lovely, melancholy tunes and poetry with exquisite sensitivity to text and meaning. His First Book of Songs or Ayres became a phenomenon when it was published in 1597, as was his Second Book, appearing in 1600 and attracting scores of fans and emulators. “English lute songs” became instantly beloved.

And continue to be. Musicians as far on the early-music periphery as Sting, singer/songwriter with the ‘80’s English rock band The Police, see him as a forefather. “Dowland’s music has a kind of DNA,” Sting wrote in 2006 on recording a selection of Dowland songs. “Played on the lute, The Beatles, Elgar and myself, you can recognize an affinity with John Dowland.”

But 17th-century English music without words is equally eloquent. English ayres, dances and “fantasias” forged new horizons for expression in instrumental writing. Those fantasias are among the period’s musical wonders. With no fixed requirements for musical form, they offered unprecedented creative freedom to composers. Thomas Morley, an early practitioner, makes a surprisingly modern case for fantasias as self-expression:

…a musician taketh a point at his pleasure, and wresteth and turneth it as he list, making either much or little of it according as shall seem best in his own conceit. In this more art may be shown than in any other music, because the composer is tied to nothing, but he may add, diminish, and alter at his pleasure.

A Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musicke, 1597

A daring moment in music

English composers rose to the challenge of this new music with eagerness. William Lawes, an artist exceptional for the vividness and daring of his musical writing, throws every compositional, harmonic, melodic trick imaginable into his collection of instrumental music for six players, The Royal Consort. As a result, the “Fantazy” from that collection’s set no. 6 sounds for all the world like an unscripted, real-time journey through an individual’s thoughts, emotions, and desires—as if six people playing together on diverse instruments were somehow on the same wavelength, spontaneously winding thoughts together into a single, ever-changing, multi-colored skein. It’s an amazing moment in music.

The early 17th century was indeed a high-water mark in English musical culture. At the same time, though, society outside was complicated and disturbing. During these first decades of the 1600s, the 30 Years War ravaged continental Europe while 17th-century England entered a long period of civil unrest culminating in the 1640s with Civil War and the execution of King Charles I. William Lawes himself was killed as a soldier in Charles’ army. .

Nonetheless, the era’s music celebrated individual creativity and the human spirit with a brightness that has rarely been equaled. Times may have been dark, consorts may have been broken (metaphorically if not actually). But the musical achievement of the era is very solid indeed.

______________________________

Anne Schuster Hunter is a writer and art historian living in Philadelphia. She offers a creative writing workshop at Temple University Center City. www.anneschusterhunter.com.

Note:

Each page provides music for playing with lute alone or with consort, and arranged the parts on the page for players reading them around a table.