Commedia dell’arte emerged around the middle of the 16th century as the first professional theater form. The Italian arte here translates as “profession” or “craft,” distinguishing it from more amateur theatre forms such as pageants and festival plays.

Commedia plots revolve around the interaction of several stock characters, whom audiences recognized instantly thanks to their distinctive physicalities and, critically, their iconic leather half-masks with features unique to each character.

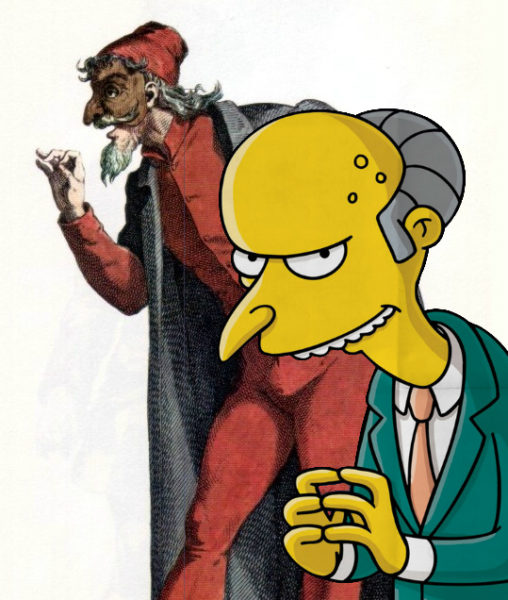

Masks are central to the identity of the commedia characters, so much so that the Italian word for stock character is maschera (mask). For example, mischievous, constantly hungry Arlecchino (Harlequin, pictured), wears a black mask with red cheeks, a small, puglike nose, and raised eyebrows, emphasizing the character’s childlike sense of wonder. Capitano’s mask is an angry red, echoed by a furrowed brow, and features a long, pointed nose meant to evoke a sword or, given the risqué nature of much of the humor, something else entirely. He frequently has a large moustache of animal hair designed after the fashion of whatever foreign nation he pretends to be from.

Because the masks cover all of a performer’s face except the mouth, commedia acting is a whole-body experience. Surprise is evoked by leaping fully into the air, mouth wide. Anger is expressed by stomping around the stage, gesticulating furiously. A character beset by grief is likely to collapse dramatically onto the ground, shoulders shaking and fists beating the stage.

The masks also limit eyesight, forcing commedia actors to turn their entire head to follow the action. This makes for swift, dramatic shifts in focus as various long-nosed masks swivel around the stage, pointing towards whatever is central to the scene at any given time. It also gives the characters an animalistic aspect that is further emphasized by their styles of movement: Pulcinella’s jerky, headbobbing walk, for example, gives him his name “Little Chicken;” and the flighty, cooing serving woman Columbina’s name translates to “Dove”.

Commedia dell’arte performances are improvised, following a rough plot outline called a canovaccio (canvas), once literally sketched on a sheet of canvas and hung in the theater’s wings to allow the actors a reference point for their improvisations.

Most commedia plots follow a few basic patterns, but the core trope is always the conflict between master and servant characters. Almost every stock character is a complete idiot, though their individual brands of stupidity vary wildly, from characters like Pulcinella and Mezzetino, whose nearly-clever schemes never work as intended, to the moronic and lustful Zanni, who is only slightly more intelligent than the average rock.

A pair of young lovers often feature at the center of the drama. Called the innamorati, they are the children of rival masters—frequently the miserly Pantalone and the pompous Dottore, who fancies himself a scholar—and their forbidden love pushes them to send their servants into misadventures. Letters go to wrong addresses, lust drives characters astray, and everyone ends up furious with everyone else before some series of mishaps delivers the whole idiotic bundle to a relatively happy conclusion.

Commedia is risqué, with sexual humor forming the basis for much of the genre’s comedy alongside stock gags, called lazzi. These lazzi form a large part of an actor’s repertoire, ready to be used whenever they might add to a show. One example involves foreign language, in which a character pretends to speak a tongue but just ends up spouting gibberish. Arlecchino or Zanni characters often use the “lazzo of the fly”, in which they are so overcome by hunger that they catch and delicately eat a fly as though it were a gourmet meal.

Most commedia actors specialize in a single character. Some historical performers’ takes on characters became so iconic that imitations of their performance became stock characters in their own right (think of Marlon Brando’s Vito Corleone and its influence on later portrayals of mobsters). As a result, troupes emphasized certain stories over others to give their star men or women greater prominence. And yes, women were prominent on the commedia stage, unlike their contemporaries in Shakespeare’s England, who were banned from performing. In fact, several commedia actresses became incredibly famous in their time, recognizable throughout Italy and France as A-list celebrities.

As commedia dell’arte aged, it evolved. First, playwrights like Carlo Goldoni and Molière took the characters and wrote structured plays with lines and stage direction, removing the improvisation that was once core to the form. As other influences crept into comedy, certain characters faded from prominence as others rose to the fore. In France, the once minor Pedrolino became the popular Pierrot, whose white-painted, sad-eyed face was the ancestor of many modern circus clowns and mimes. Eventually, commedia faded from the spotlight.

But that’s not to say it disappeared altogether. Classical commedia is still performed today, as are more modern variants on the themes, but the form also has its fingers in much of Western comedy. The Three Stooges, for example, have much of the buffoonish Zanni in them (note the word “zany”, which is a direct descendant), and Basil Fawlty of Fawlty Towers is about as Brighella as it gets, lording over the servants under him and sucking up to his customers above him. C. Montgomery Burns of The Simpsons is a classic Pantalone down to his physical posture and age, and the swagger, bravado, and sheer incompetence of Arrested Development’s G.O.B. Bluth is Capitano through and through. And, of course, every instance of slapstick humor owes something to the commedia stage—the word “slapstick” itself comes from Arlecchino’s everpresent club.

Tempesta di Mare’s program Fantaisie: Orchestral Storytelling and Imagination is deeply tied to the characters, stories, and humor of commedia dell’arte. Listen as Telemann’s coquettish siciliana captures the spirit of Columbina (Columbine in the French) and his clownish gavotte imagines the awkward, sadsack Pierrot. Picture yourself at a show of slapstick humor and hilarious escapades, as servants, masters, lovers, and fools gallop around the stage with Kusser’s music filling the air. And remember the immortal words of William Shakespeare: “Lord, what fools these mortals be.”

_____________________________

Rafael Schneider is an actor and musician from Philadelphia. He studied Commedia dell’Arte at the Accademia dell’Arte in Arezzo, Italy.