The story of Judith and Holofernes can only be called a Ripping Yarn. Although it’s 2000 years old, first having appeared in the first Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, 100 BCE, it’s a story that’s cycled and recycled through western culture ever since, with retellings in every medium imaginable. Understandable: it’s Mulan meets Lizzy Borden. The treatment practically writes itself.

British Museum YT 20, f. 215; Public domain

In summary, the story is about Judith, a young Jewish widow, who lives in a city besieged by foreign troops. To persuade the invading general, Holofernes, to retreat, she visits him in the enemy camp. He wines and dines her, to which she reluctantly submits, but when he falls into a drunken stupor mid-seduction, she grabs his sword, beheads him and thereby frees her people.

the women who became the heroine

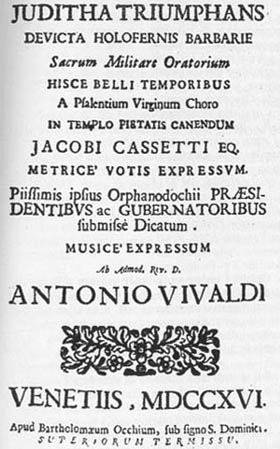

Tempesta di Mare presents Antonio Vivaldi’s baroque opera treatment of the hallowed story in the oratorio Juditha Triumphans from 1716. It’s a piece he wrote specifically for the singers and orchestra of Venice’s Ospedale della Pietà, all of them women, orphans, and permanent wards of the institution. The choice of subject for them makes sense, as a great piece for women about a great heroine.

You have to wonder, though. Because of high and honored position in Venetian society, the Ospedale della Pietà’s Board of Governors was so concerned with maintaining the purity and very appearance of purity of their wards that it even forbad its musicians to perform in public without staying hidden behind curtains or masks. An oratorio—essentially a concert opera—in high baroque style, you’d think would be high stakes. Why did they indulge in such potentially racy, gory fare?

Autres temps, autres mœurs—other times, other mores, probably. Everybody knew the old story, in some respect, its sharp edges had long since been rubbed off.

Judith, Icon of Her Times

But the angles Vivaldi and his librettist—and perhaps the Ospedale—chose for their version of the tale, well, that’s interesting. It says a lot about the time. But it says even more about Judith as a figure whose power as a symbol is still very much with us.

First, the Ospedale had a straightforward reason for choosing Judith. In the story, because Judith defeats an over-matched foe, Holofernes, she had long ago become a symbol of successful military triumph over long odds. Only months before Juditha Triumphans’ premiere, the Republic of Venice won an important victory over the Ottomon Empire on the Isle of Corfu and the oratorio is a direct tribute to it. The oratorio’s librettist salutes it in the finale:

“Thus, by everlasting decree, I have deemed

the maritime city of Venice to be undefiled”, sings Holofernes’ henchman,

“Now that this virgin city is evermore protected

from the godless tyrant Holofernes in Asia,

thanks be to God, it will hence be “New Judith”.

Second is a reason that was probably straightforward then but more obscure to us now. Because Judith spurned Holofernes’ advances and prevailed over his evil, she was held as a conventional model of female purity and piety, a moral example to womanhood as a defender of good values. You have to downplay the murder, though. Botticelli’s Judith with the Head of Holofernes of c. 1470 gives us a nice image of this side of Judith: she walks away from the murder site seemingly unperturbed, eyes soulful, beautiful gown spotless and the general’s head tucked neatly away in a basket on her assistant’s head.

“Merciful Father in heaven…,” prays Vivaldi’s Juditha, justifying the act she’s about to commit,

“…help us in our prayer, and take away our guilt,

and from your strong right hand,

Judith for Justice

Then there’s the third reason and this is one that has made Judith a vital presence now: the portrayal of Judith as a fierce fighter for justice. Vivaldi and his librettist soft-pedal to some extent in Juditha Triumphans, but it’s there, the murder takes place right on stage, figuratively.

And elsewhere in baroque culture, the messy parts of the Judith and Holofernes story were overt, even brazen. Painting in the 17th-century had taken old medieval iconography and ushered in a new era of fiery Judith, Roman painter Caravaggio leading the way. Painter Artemisia Gentileschi pushed Caravaggio’s example further, producing one of the most fiery Judiths, her Judith Beheading Holofernes of 1620. Artemisia’s bloodspattered heroine is determined and resolutely physical, overpowering her victim as he attempts to fight back. This is a fierce, indomitable fighter for justice.

And this Judith went viral in the second millenium CE—literally. Artemisia’s Judith has become not only one of the best-known images from the baroque era, but a present-day icon of women battling injustice. At the height of #MeToo, her Judith and Holofernes was inescapable. It still circulates and recirculates on social media. I saw it go by yesterday.

In 1716, Vivaldi’s librettist wrote a sweet valediction about how Judith’s heroism would grow and prosper:

“Return now, victress, return to battle,

reinvigorate in sackcloth, in prayer.

For having bested Holofernes today,

Live on, dear Judith, for the ages!”

The prophecy has been fulfilled. Judith indeed lives on, for the ages.

Anne Schuster Hunter is a writer and art historian in Philadelphia. www.anneschusterhunter.com.

Libretto translations by Richard Stone with permission

Palazzo Barbarini, Rome, Wikimedia Commons