At some point, I hope, this work will make me famous….”

Georg Philipp Telemann, 17321

When Telemann wrote this to a friend in 1732 about his chamber music collection Musique de Table, it was an unexpected comment. Telemann was already famous. At age 51, he had fans all over Europe and a huge catalogue of work that included weighty efforts like a full-length Passion. But it’s not one of those ambitious projects that he pegs as his bid to posthumous fame. It’s chamber music.

SMALL SCALE – BIG HEART

Tempesta di Mare’s Unmatched brings together chamber works—small-scale works—by Telemann and other composers that are, in fact, bringing present-day fame to their composers. Umatched spotlights a particular configuration of chamber music. The instruments involved are from different families—double reeds, flutes, strings—which the composers employ one-on-a-part and with and against each other in various permutations. Unmatched demonstrates how, when the distinctive timbres of baroque instruments voices are mixed, matched and mingled by inspired composers and skilled players, they provide a feast for the ears that can put larger productions to shame.

These works may be small-scale. But they have big hearts.

Given a steady demand from amateurs and professionals for new material for home music-making and gigs, there was a lively market for chamber music in the baroque. For composers so inclined towards the genre, this was a great moment.

ELBOW GREASE

As he tells us, for instance, Telemann’s attachment to chamber music was deep. He seems to have simply liked instruments, could take pains to write to their best effect—and was an enthusiastic instrumentalist in his own right. He mentions in an autobiographical sketch that by his ‘20’s, he was proficient on keyboard, violin, voice (baritone), recorder, oboe, traverso, chalumeau (baroque clarinet), viola da gamba, contrabass, and bass trombone. And he worked at them, too. Describing the pains he took to be able to play second fiddle to a virtuoso he admired (and had the wonderful name of Panteleon Hebenstreit), he says:

…whenever we had to play a concert together, I would lock myself in my room, my left shirtsleeve rolled up and my arm smeared with nerve ointment, and practice hard in order to be able to hold my own against him. Sure enough! my playing improved a lot.“2

THE ‘GREEN VAULT’ OF MUSIC

It stands to reason that some of Telemann’s collections, including Musique de Table, are now considered among the gems of mixed chamber music. But they are hardly alone. Unmatched presents a cornucopia of works by composers from a wide geographic area and a two-generation chronological span who clearly found the possibilities of “unmatched” chamber music compelling.

Among them is a trio sonata by the Czech composer Jan Dismas Zelenka, who played bass with the legendary Dresden Hofkapelle and, as the Dresden court’s church composer, would go on to create some of its biggest, most solemn liturgical works. Before that, though, in the 1730’s, he worked out his ambitions in chamber music (in a collection that is notoriously challenging to perform). Antonio Vivaldi is represented with a chamber concerto for five parts that contains thrilling examples of his passagework; he knew it was safe to write them because the crack all-female instrumentalists of Venice’s Ospedale della Pietà3, with whom he had a long relationship, could handle them with aplomb.

International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

North German Johann Friedrich Fasch demonstrates that he could indulge his genius for instrumental color in chamber works just as well as he did in works for orchestra. A generation younger, Johann Gottlieb Janitsch’s relatively unusual choice—at that date—of possibly including a recorder at the lineup for his Quadro reflects his sensitivity to tastes in the Berlin salon environment4 he inhabited.

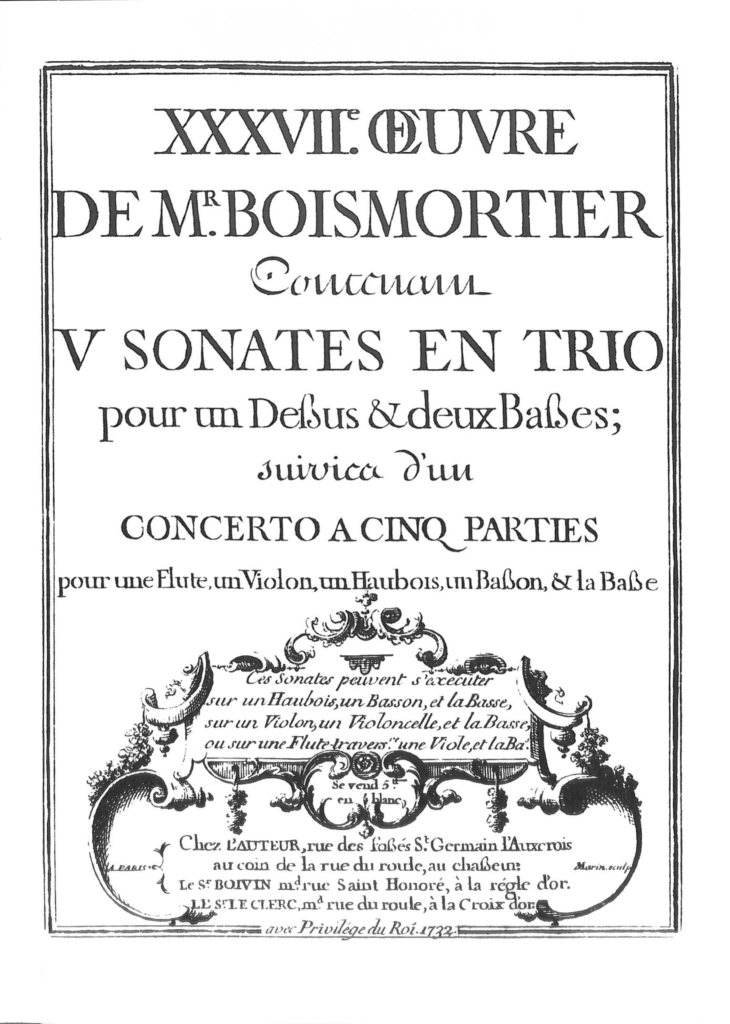

And then there’s Joseph Bodin de Boismortier. A participant in the super-heated, super-chic musical salon culture of Louis XV’s Paris, Boismortier provides a suitable finale to the Unmatched program. His Op. 37 contains five sonatas that combine a treble and a low instrument, an octave apart, as a pair over continuo; he stipulates that the instruments be matched, that is, in the same family. What Tempesta plays, though, is the collection’s concluding concerto, where Boismortier tosses out decorum and adds two more thorough unmatched trebles to the mix—a salute to chamber music ingenuity.

Cold weather brings its own kind of beauty. Its pleasures may be smaller and quieter than in summer, but as if in compensation, they seem deeper. Hot spiced coffee is more delicious in winter. Birdcall seems more intense. A handful of hardy red roses and morning glories, powdered with frost but still blooming beautifully, perform all the glories of the garden in their few, singular selves. There’s a metaphor there for chamber music.

Which is why without a holiday song in sight, Tempesta di Mare may be providing the perfect midwinter celebration with Unmatched.

Anne Schuster Hunter is a writer and art historian in Philadelphia. www.anneschusterhunter.com.

FOOTNOTES & LINKS:

- From a letter from Telemann to J. R. Hollander in Riga (undated, probably winter 1732/3). Georg Philipp Telemann, Briefwechsel, ed. Hans Grosse and Hans Rudolf Jung (Leipzig, 1972)

Diss Werk wird hoffentlich mir einst um Ruhm gedeien…(Translation by the author) ↩︎ - From Telemann’s 1740 autobiography, in Johann Matheson, Grundlage einer Ehren=Pforte, Hamburg 1740, p. 354-369:

…dass, wenn wir ein Concert mit einander zu spielen hatten, ich mich etliche Tage vorher, mit der Geige in der Hand, mit aufgestreifftem Hamde am lincken Arm, and mit stärckenden Beschmierungen der Nerven einsperrte, und bei mir selbst in die Lehre ging, damit ich gegen seine Gewalt mich in etwas empören könnte. Und siehe da! es half zu meiner mercklichen Besserung. (Translation by the author) ↩︎ - More about the All-Girl-Band at the Ospedale della Pietà: Women behind Screens

↩︎ - More about the Berlin Salons of the Itzig Sisters & Janitsch: A Fuller Story | The Itzig Sisters ↩︎